Why I Moved Away from Glycemic Index as Important to Appetite … an Illustration of the Evolution of Scientific Thinking

Conclusions in science are always tentative based on the data. When presented with new data, a scientist evaluates that new data against the current body of data, and determines whether current conclusions are supported or should be modified or overturned.

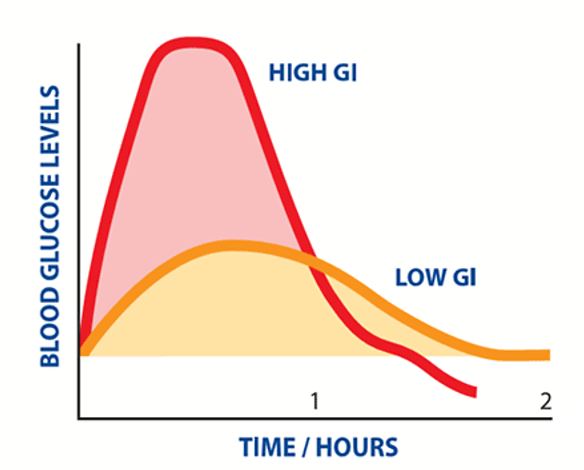

As late as the mid 2000's I was a believer in the insulin hypothesis of fat gain/obesity. As I examined more and more data, it became very clear to me that the insulin hypothesis was completely wrong, so I ditched it. I was also a believer in the glycemic index and its impacts on appetite. However, further examination of data indicated that the GI had minimal impacts on appetite, so I ditched it. In fact, this falls in line with my ditching of the insulin hypothesis (where one aspect says that high carb foods create insulin spikes, leading to reactive hypoglycemia and hunger/overeating).

I wrote this as a comment in another post I made but felt it bears reposting here. It illustrates the accumulated data which overturned my thinking regarding the glycemic index and appetite.

There's been a number of studies over time that have led me away from considering GI as an important factor in appetite regulation (I used to believe it was, but there's too much data that has made me change my mind).

One of the first studies in fact was done by Jennie Brand Miller, one of the big GI proponents. They tested 38 different foods and looked at factors that predicted satiety. GI was not one of them. Rather, energy density, protein, fiber, and palatability were predictors of satiety.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7498104

In another study by the same authors, glucose responses were not predictive of satiety.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8968699

In a meta-analysis of studies, glucose responses were not predictive of satiety.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17524176

Energy density and fiber are big confounders in GI studies. When you control for these things, the impact of GI is either weak or non-existent.

For example, in this study, which controlled for energy density, macro nutrient content, and fiber, a low GI meal only had a very small effect on feelings of fullness, and there was no impact on actual energy intake.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21775528

In this ad lib study which controlled for the same factors, there was no impact on satiety.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17923862

Another ad lib study which controlled for these factors, with no impact on satiety

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15277154

In an extremely well controlled, well designed 8-day study in the lab, which controlled for macronutrient content and palatability, GI was not related to appetite ratings or food intake.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16123477

On top of all that, it's been found that the GI of a particular food is highly variable from one person to the next, and even highly variable from day to day within the same person, making it unreliable.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23822709

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18186950

For all of these reasons, I do not consider the GI a very useful tool in constructing high satiety diets. On top of that, being focused on GI can lead people to avoid certain high GI foods that are, in fact, very satiating and nutritious (like potatoes).

Appreciate this amazing article. I needed this information to dispute influencer posts about the wonders of resistant starch, why we needed to freeze our breads and then defrost to have lower glucose responce. Thank you again.