A recent study out of Princeton University has the high-fructose corn syrup alarmists out in full force. This study compared the effects of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) to regular table sugar (sucrose), looking at their effects on body weight, body fat, and triglycerides (fats that float around in your blood). The study found that the rats fed HFCS gained more weight and abdominal fat than the rats fed sucrose. This study has strengthened the belief of some people that HFCS is contributing to obesity in our society, and that it is worse than regular sugar. But is it really?

To answer this question, we need to take a close look at this study. The researchers performed 2 experiments. In the first experiment, male rats were divided into 4 groups. Group 1 (the control group) was fed a regular diet. Group 2 was fed the same diet, with the addition of 24-hour access to water sweetened with HFCS. Group 3 had the regular diet with 12-hour access to the HFCS-sweetened water. Group 4 had the regular diet, with 12-hour access to sucrose-sweetened water. The rats were tracked for 8 weeks; weight was measured, along with food, sucrose, and HFCS intake.

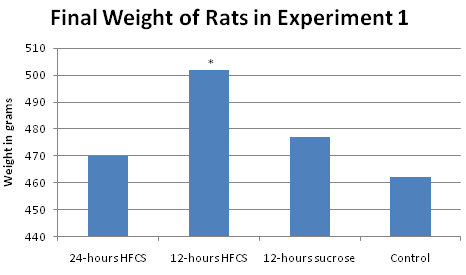

You can see the results for experiment 1 in the following chart:

The rats who got HFCS for 12 hours gained significantly more weight than the other 3 groups. At first glance, this would make you believe that HFCS makes you gain more weight than sucrose, even if you are eating the same number of calories. However, there is a problem with these results. Take a look again at the chart above. If the rats fed HFCS for 12 hours gained more weight, why didn’t the rats fed HFCS for 24 hours also gain more weight? They got HFCS for a full 12 hours more, yet didn’t gain more weight. This is a glaring inconsistency in the results…an inconsistency that the researchers never tried to explain.

Rather than some unique effect of HFCS, a more likely explanation is one of chance. Put on your math hat, because we need to talk about some statistics. Researchers use statistics to get an idea of the probability that their results are due to chance. When the scientists run their stats, they get what is known as a P value. The P value tells you the probability that the results are not due to chance. Usually, if the P value is less than 0.05, a scientist will call the results “significant.” In other words, if you did the experiment 100 times, you would only see these results less than 5 times if there wasn’t a true effect.

The above only holds true if you’re doing a single comparison. If you start comparing a bunch of groups all to each other, the probability of a fluke result dramatically increases. The Princeton study is a perfect example. There are 4 groups all being compared to each other. That makes for 6 total comparisons (group 1 to group 2, 1 to 3, 1 to 4, 2 to 3, 2 to 4, and 3 to 4). Each one of these comparisons is being tested against that 5% level. To calculate the probability of a fluke result in this case, we calculate 1 – (0.95x0.95x0.95x0.95x0.95x0.95) = 26%. In other words, there is a 1 in 4 chance that the greater weight gain in the HFCS-fed rats is a fluke. I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t put too much faith in results that have a 1 in 4 chance of being wrong. There are ways that scientists can adjust for this, but the Princeton researchers didn’t appear to make those adjustments. Thus, it is not surprising that there was a significant result observed in 1 out of the 4 groups…you would expect this to happen based on random chance alone.

In Experiment 2, the researchers divided male rats into 3 groups: 12-hour HFCS, 24-hour HFCS, and control. They tracked the rats for 6 months. Both HFCS-fed groups gained more weight and fat than the control, and also had higher triglycerides. However, the researchers didn’t compare HFCS to sucrose in this group, so this experiment doesn’t’ say anything about whether HFCS is any worse than sucrose. The researchers also didn’t say anything about food intake and whether the HFCS-fed rats ate more than the control rats.

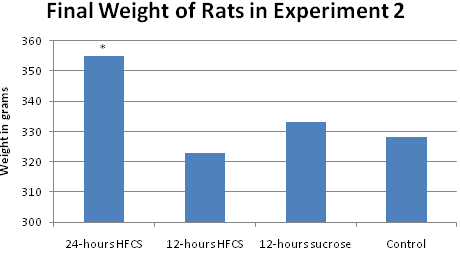

Experiment 2 also featured female rats on one of the 4 diets used in Experiment 1. These rats were tracked for 7 months. The following chart shows the results of the experiment:

The female rats fed HFCS for 24 hours a day gained significantly more weight than the other groups. Now compare these results to the chart for Experiment 1 earlier. Do you see the disparity? In Experiment 1, the rats fed HFCS for 12 hours per day gained the most weight. However, in Experiment 2, the rats fed HFCS for 24 hours per day gained the most weight, and the female rats fed HFCS for 12 hours didn’t gain any more weight than the other groups. Why did the 12-hour group gain the most weight in one experiment, but the 24-hour group gain the most weight in a nearly identical experiment? This is a glaring contradiction in the results, and a problem which the researchers did not discuss. We also have the same statistical problem that we did with Experiment 1. Since there are 6 comparisons, there is a 1 in 4 chance that the results are wrong (and ironically, we have 1 out of the 4 groups showing a significant result). In fact, when we take both experiments combined, we have at least a 50% chance that the results of one of the experiments are wrong. Out of all the comparisons being made, we would expect to see a couple groups show a significant result based on random chance…and that’s exactly what happened in this study.

The bottom line is that there is no valid reason for HFCS to be any different than sucrose in the way that it affects your body. They are both nearly identical in their composition, containing roughly half fructose and half glucose. They are both nearly identical in the way they are metabolized by your body. There is no practical difference between the two as far as your body is concerned. Now, I’m not saying that you should go out and consume all the HFCS that you want. The point is that there is nothing uniquely “bad” about HFCS compared to regular sugar. HFCS is not uniquely responsible for weight gain as some people would have you believe.

If you see a product with HFCS and a similar product with natural table sugar, don’t assume the product with natural sugar is any better. Rather than worrying about whether something contains HFCS, you should strive to reduce your intake of all types of added sugar and refined carbohydrates in your diet. It is much more important to look at the big picture; keep your physical activity high, manage your overall food intake, make sure most of your food is from minimally refined sources, and keep your protein intake high. This is what will help you lose weight and keep it off, rather than singling out HFCS in your diet. Don’t let the fructose fear-mongerers fool you.

I would really like to be able to go to a cannabis social

association while visiting, so please let me know what I should do!

I boycotted HFCS many years ago because I read that it made you fat. I wanted to lose weight and protect my heart because of the large number of heart attacks on my side of the family. Imagine my surprise upon returning home from work one day to find my active healthy-looking trim husband, who’d had no heart problem history, in the beginning stages of a massive heart attack. He had 90% blockage in the artery known as the “widow-maker” and his triglycerides were off the chart. He survived. That led me to question our diets, the major difference of… Read more »

Hello to all, how is the whole thing, I think every one is getting

more from this web page, and yoour views are pleasant designrd for new users.

This site was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I have found something which helped me.

Thank you!

My website; certificate of use inspections miami fl

I tend to agree that there is no single culprit — and by the same token, no single cure — for obesity. Two generations ago children grew up on sweetened cereal, but were able to stay slimmer than their counterparts today.

I’ve lost 50 pounds and maintained the loss on a high-carb diet (with most of my carbs in the form of whole grains), while people all around me are demonizing carbs. Carbs make me feel uniquely satisfied, both physically and psychologically, so I see no reason to give them up if what I’m doing is working.

Congrats on your success, Gabrielle! Thanks for your comment as well.

James,

you said:

” If the rats fed HFCS for 12 hours gained more weight, why didn’t the rats fed HFCS for 24 hours also gain more weight? They got HFCS for a full 12 hours more, yet didn’t gain more weight.”

this is how they explain it in the full text:

“We selected these schedules to allow comparison of intermittent and continuous access, as our previous publications show limited (12-h) access to sucrose precipitates binge-eating behavior”

However it does not make sense anyway, as their own long-term study shows the opposite

Thanks for that, Tomas. I completely agree with you that no matter how you look at it, it doesn’t make any sense.

James,

I am not familiar with the statistics terms, so this comment is based solely on the information in your article. based on my understanding from your article, the pair wise-calculated p-value of ~0.25 in dictates that one of the four sample groups could have happened by chance. is it possible that the 24-hour group in Experiment 1 was low by chance and that the 12-hour group was correct? If so, then wouldn’t the results be inconclusive of the presence or absence of effect from HFCS?

Hi, Bob, When doing statistics such as these, you are always testing the null hypothesis. In this case, the null hypothesis is that there is no difference between any of the groups. The alternative hypothesis is that a difference exists. You need sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative. A significant P value means you have sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis. However, if that P value is significant because you didn’t adjust for multiple comparisons, then there is a good chance that you falsely rejected the null hypothesis. In other words, it’s a false… Read more »

I think everyone has forgotten that fructose is MUCH sweeter than glucose or sucrose. So any mixture with free – and an excess – of fructose is more likely to be addictive (sugar sure seems to act in the same centres as cocaine and nicotine doesn’t it? Is that glucose or fructose?) in well formulated food and drink. When HFCS was developed, the big food companies did not do an equivalent sugar substitution based on sweetness did they? They INCREASED the dose (because it was cheaper) because it increases addiction – and sales. Sweetness is perceived in the mouth. So… Read more »

I appreciate your being the Devil’s advocate regarding Dr.Lutig’s “Sugar: The Bitter Truth” above. I’ve always been an advocate of Mark Twain’s “Lies, Damned Lies and Statistics”… Your final comments are key to your rebuttal, i.e. ” It is much more important to look at the big picture; keep your physical activity high, manage your overall food intake, make sure most of your food is from minimally refined sources…” How do we convince people to do that?

Thanks, rkeinc. I’m not sure how we convince people to do that. I think it’s human nature to want to point our fingers at one thing thing that is causing obesity. People want a scapegoat, and in this case it’s HFCS. It’s tough to fight human nature and I think we’re always going to deal with the problem of people losing the forest for the trees.