Periodization / Variation in Repetition Ranges for Muscle Size: Your Complete Evidence Based Guide

Maximizing muscle growth means manipulating your training variables to create the best stimulus possible. These variables include volume, frequency, intensity, rest intervals, and others. Periodization refers to the programmed manipulation of training variables in a systematic fashion to help maximize adaptations. In the world of weight training and building muscle, periodization often is synonymous with varying your repetition ranges and loads over a specific time frame. In this evidence based review, I'll go over the theoretical reasons why varying your rep ranges may, or may not, help you build muscle. I'll then look at studies that have specifically addressed this question. As with other Weightology evidence-based reviews, you'll come away with a set of principles that you can practically apply to your own training or that of your clients.

Key Takeaways

- As long as sets are taken to failure or near failure, muscle fiber recruitment and muscle protein synthesis are similar between moderate and high rep sets, suggesting no benefit to variation of rep ranges.

- Four studies show no benefit to variation, 2 studies show a slight benefit to undulating periodization over linear periodization, and one study shows a slight benefit towards linear periodization over undulating periodization. This suggests no clear benefit to periodizing repetition schemes over keeping them constant.

- These points assume you're training with sufficient volume in the first place; some data suggests that the prolonged periods of low volume/high load training in linear periodization schemes may not be as good for hypertrophy.

Practical Application

- There is no good evidence of a benefit to periodization or variation in rep ranges for increasing muscle size over more constant rep schemes, as long as you are training with sufficient volume to maximize hypertrophy.

- Prolonged periods of high load/low rep training, such as what can happen in linear periodization schemes, may not be optimal for hypertrophy.

- The benefits of rep range variation/periodization for hypertrophy likely lie in reducing joint stress/injury risk (to help with training consistency) and improving motivation through increased variation/reduced boredom.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- The Theoretical Case for Varying Your Rep Ranges

- The Theoretical Case for "It Doesn't Matter"

- Enough With Theory...What Happens in Real Life?

- Putting It All Together

- Practical Application

The Theoretical Case for Varying Your Rep Ranges

Your muscles are made up of individual muscle fibers. There are two primary types of muscle fibers: fast-twitch fibers, and slow-twitch fibers. If you want to maximize muscle growth, you want to maximize hypertrophy of both fiber types. Research out of Russia has shown that fast-twitch fibers show more hypertrophy with heavy loads as compared to light loads, while slow-twitch fibers show more hypertrophy with light loads as compared to heavy loads. This would imply that you would want to use a combination of both heavy and light loads to maximize hypertrophy of all fiber types.

Heavy load training is superior to light load training for improving strength. This is because heavier loads result in greater neural adaptations (i.e., adaptations in your nervous system that allow you to generate more force, with no change in muscle size). This would imply that use of heavy loads can lead to greater strength gains over time, which, in turn, would allow for greater volume loads over time. Because of the relationship between volume load and hypertrophy, this would theoretically enhance muscle gains over an extended period.

Interestingly, though, it's been shown that light load training results in greater increases in volume load over time compared to heavier loads. This, theoretically, would enhance muscle gains over time due to the accumulated volume. Given the impact of heavy loads on strength, and the impact of light loads on load volume over time, it would make sense that, to optimize hypertrophy, you would combine heavy and light loads in your training plan.

The Theoretical Case for "It Doesn't Matter"

Even though Russian research has indicated that slow-twitch fibers grow more with light load training, and fast-twitch fibers grow better with high load training, other studies have not shown this. In one study, there were no statistically significant differences in changes in slow-twitch and fast-twitch fiber size between light and heavy load training, although percentage changes for slow-twitch fiber growth were favored in the light load group. In another study by the same research group, there was not even a hint of a difference in changes in slow-twitch and fast-twitch fiber size between heavy and light load training. In a third study, there were no differences in slow-twitch and fast-twitch hypertrophy when 4 sets of 3-5 RM loads were compared to 3 sets of 9-11 RM loads.

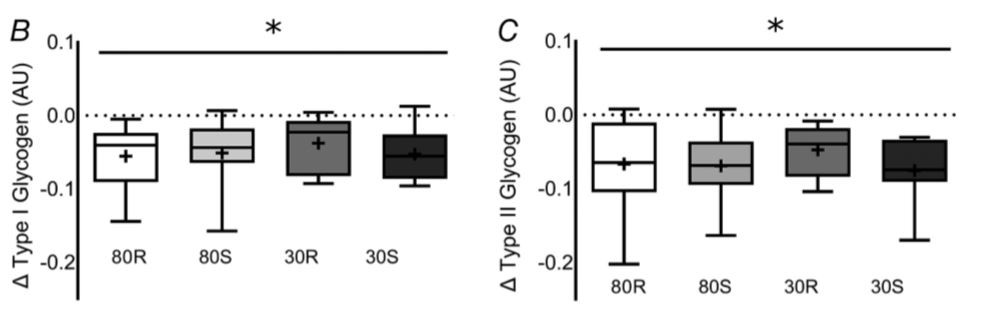

Finally, as long as sets are taken to muscular failure or near failure, muscle fiber recruitment is likely similar between heavy loads and light loads. In fact, recent research by Robert Morton and colleagues corroborates this. In this study, the scientists compared muscle glycogen (a carbohydrate stored in your muscles that fuels resistance exercise) depletion in fast and slow twitch muscle fibers when heavy loads (80% 1-RM) were taken to failure compared to light loads (30% 1-RM) taken to failure. Depletion of glycogen was similar between the heavy and light loads, indicating the two loading schemes resulted in similar recruitment of slow twitch and fast twitch fibers.

Change in Type I (slow twitch) and type II (fast twitch) muscle fiber glycogen from Morton et al. (2019). 80R = 80% 1-RM regular tempo. 80S = 80% 1-RM slow tempo. 30R = 30% 1-RM regular tempo. 30S = 30% 1-RM slow tempo. The decrease was similar among all the conditions.

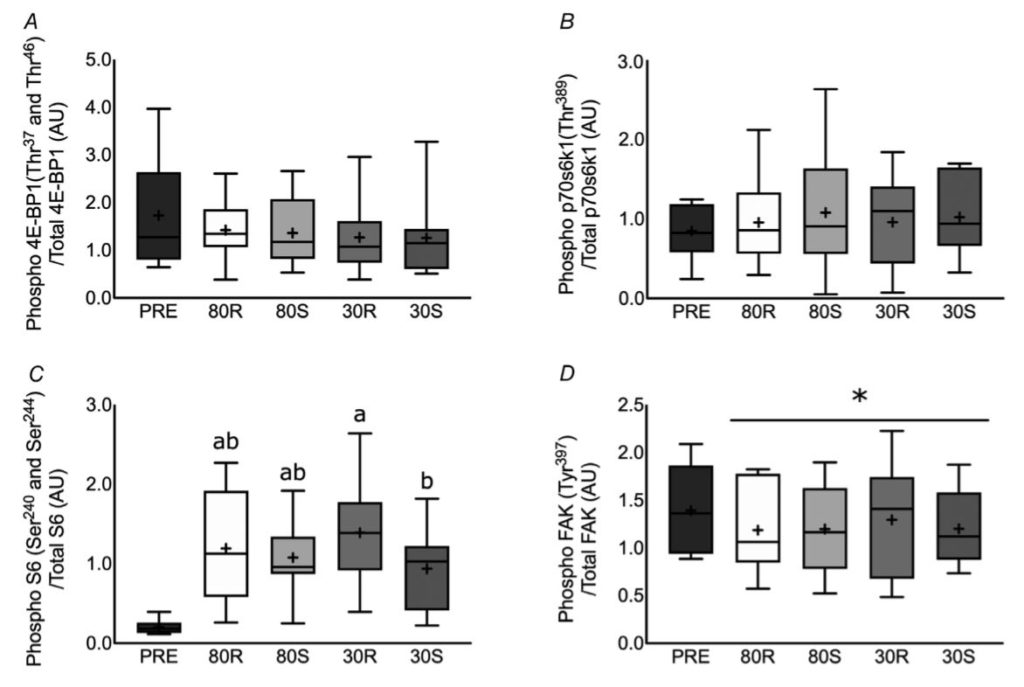

Changes in molecular anabolic signaling were also similar between the conditions.

Changes in various markers of molecular anabolic signaling in Morton et al. (2019). Changes were similar between 80% 1-RM and 30% 1-RM, whether done regular tempo (R) or slow tempo (S).

There was also a significant correlation between fast twitch and slow twitch muscle fiber glycogen depletion and p70S6k phosphorylation (a marker of anabolic signaling), indicating the recruitment and fatigue in these fibers was related to the anabolic stimulus.

Since muscle fiber recruitment and anabolic signaling are similar between heavy and light loads taken to failure, this would imply that hypertrophy should be similar between heavy and light loads taken to failure. This is exactly what has been observed in scientific studies; numerous studies have now shown no differences in hypertrophy between heavy and light weights taken to failure. This would suggest there would be no advantage towards varying your repetition range, and, as long as you are taking sets to near failure with sufficient volume, repetition range may be more a matter of personal preference.

Enough With Theory...What Happens In Real Life?

While all this intellectual masturbation over rep ranges is fun, what really matters is what happens when you take groups of subjects, put them on different training programs and see what happens. There have been a number of studies that have done this. I'm only going to look at studies with the following characteristics:

- Use of ultrasound or MRI to determine changes in muscle size. Other metrics of changes in muscle size, like body composition or circumference measurements, are too insensitive to change and/or too inaccurate to assess potential differences between training groups.

- Similar number of "hard" sets per exercise. While one might argue for equal volume load between groups, the problem with this is that volume load with light load/high rep sets is usually higher than high load/low rep sets, and you have to do 3 times the volume with light weight training to get similar hypertrophy to moderate load training when all sets are taken to failure, In other words, 3 sets of 10 RM will give similar hypertrophy as 3 sets of 30 RM, even though volume load will be much higher in the latter condition. Thus, it makes more sense to make sure that overall number of hard sets are similar, rather than overall volume load. This also means that studies that added a very high rep/low weight set on top of some regular sets, and showed enhanced hypertrophy (like this one and this one), are not included in this because it can't be determined whether the enhanced hypertrophy was due to inclusion of high repetition ranges, or simply due to additional volume/sets.

As of the latest update to this article, there are 6 studies that fit these criteria. Let's take a look at them.

- Kok et al. (2009) compared linear periodization (training periods of high reps/low weight, gradually moving to low reps/high weight as time goes on) to undulating periodization (cycling between high reps/low weight and low reps/high weight) in untrained women. The study lasted for 12 weeks and volume was equated. The overall repetition range was fairly narrow (6-10 reps), so there wasn't a lot of variation there. There were no significant differences in muscle gains between the groups, although percentage gains favored the undulating group.

- Simão et al. (2012) compared linear periodization (4 week blocks starting at 12-15 reps and decreasing to 3-5 reps) to weekly/daily undulating periodization (2 week periods of each rep range, followed by 6 weeks of daily variation in rep range). The study lasted 12 weeks, volume was equated, and subjects were untrained men. There were no significant difference in muscle gains between groups, but only the undulating group showed gains that were significantly greater than the control group, and percentage gains favored the undulating group.

- Souza et al. (2014) compared constant loads/reps (i.e., no variation) to linear periodization and undulating periodization in untrained men. The study lasted 6 weeks and volume was equated. Muscle gains were similar between the groups.

- Fink et al. (2016) compared a high load group (8-12 reps at 80% 1-RM), a low load group (30-40 reps at 30% 1-RM), and a group that alternated between high and low loads every 2 weeks. Subjects were untrained and the study lasted 8 weeks. There were no differences in muscle gains between the groups.

- Pelzer et al. (2017) compared linear periodization (2 week blocks, with sets of 15 progressing to sets of 6) to daily undulating periodization (varying between 15, 10, and 6 reps). The study lasted 6 weeks, involved trained subjects, and volume was equated between groups. I reviewed this study in a previous research review. There were no statistically significant differences in muscle gains between groups, although percentage gains and effect sizes slightly favored the linear periodization group.

- I collaborated with Brad Schoenfeld and others on a study that compared a varied repetition scheme (one day of 2-4 RM, one day of 8-12 RM, and one day of 20-30 RM) with a constant repetition scheme (8-12 RM). The study lasted for 8 weeks and involved trained individuals. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in load volume, although load volume tended to be favored in the constant rep group. There were no statistically significant differences in muscle gains between the groups, although percentage changes and effect sizes favored the varied group in the bicep and tricep muscles.

A Closer Look at the Schoenfeld Study

Let's take a closer look at that last study that I was involved in. The average changes in the arm muscles favored the varied group, but it was not statistically significant. This could mean one of two things:

- There is an impact of varied reps on changes in muscle size, but there was not enough subjects in the study to statistically detect the difference (in statistics, we would call this a type II error or false negative).

- The differences in average values are just random variance. With small sample sizes, a few outliers can make average values look very different...a difference that would disappear with more subjects.

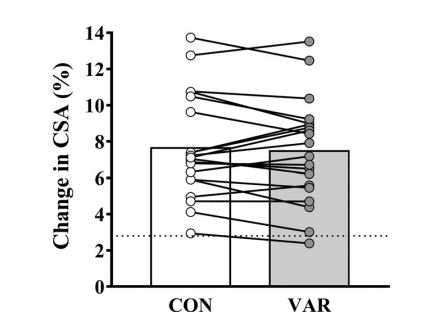

In a situation like this, it can be useful to look at a scatterplot of the individual changes. This will help us get a better idea of whether there's a true tendency for varied reps to do better, or if this is all just random variance. Most studies don't present individual results, but given that I was the one who analyzed the data in this study, I have access to that data. Thus, I'm presenting the individual results to you, and you won't find this information anywhere else.

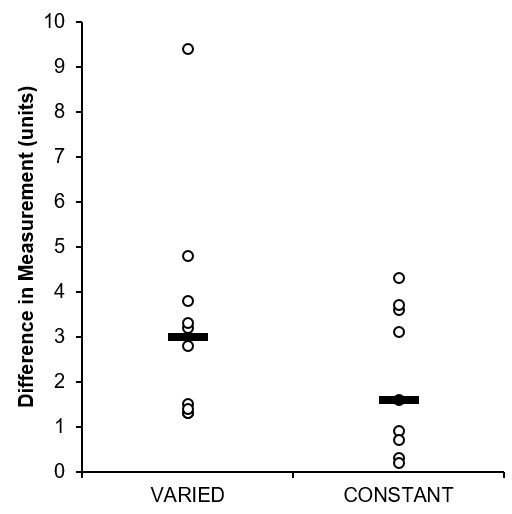

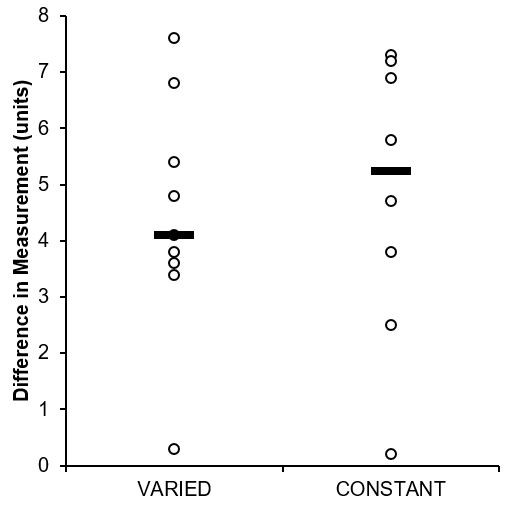

Let's take a look at the tricep muscles first. Here's a graph of the individual results. Each circle represents the change in an individual, and the horizontal bar represents the average change.

While the overall distribution of changes favors the varied group, there is one clear outlier that is pulling the average up. However, even after removal of this subject, the distribution still favors the varied group.

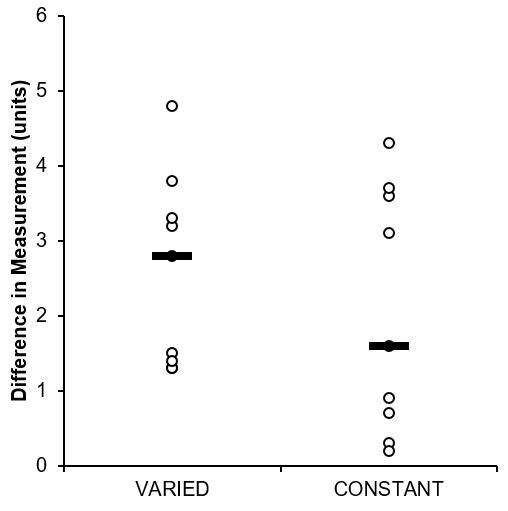

These results would suggest a benefit to varied rep training, but we need to look at the other muscle groups. If there's no clear benefit in the other muscle groups, then this would suggest that the tricep results are a product of random variance (or that only the triceps benefit from varied rep training, but I cannot think of any physiological rationale why this would be the case). Here's the results for the biceps.

In this case, there's clearly an outlier in the constant group who barely had any change. Otherwise, the distribution of the results is fairly similar. This is confirmed when we remove the outlier.

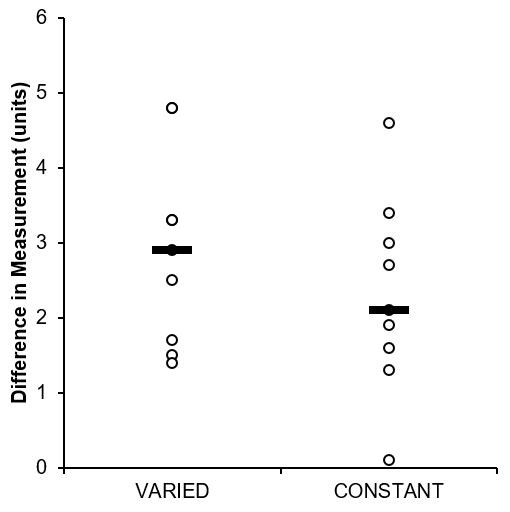

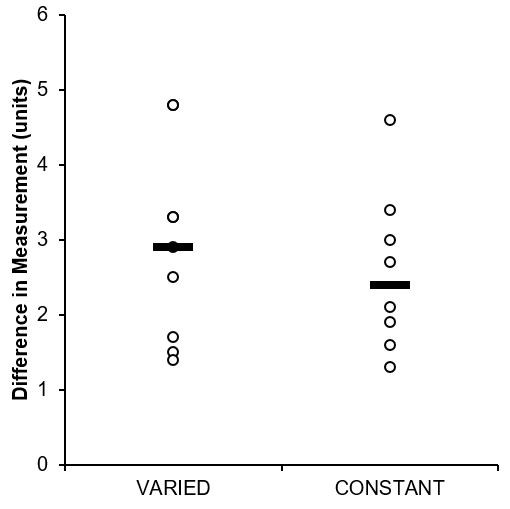

This would suggest no real benefit of varied rep training over constant rep training. Finally, let's take a look at the quadriceps results. Percentage gains were similar between the groups for the vastus lateralis. Here's the individual results.

Overall, there is no clear difference between the two groups. Thus, in 2 out of the 3 muscles analyzed in this study, there is not a clear benefit of varying your rep range. In all likelihood, the tricep results are a product of random variance. Therefore, there does not appear to be an apparent benefit to varying your rep range for hypertrophy after closer inspection of this study.

The Damas Variation Study

In an 8-week, well-designed study, Damas and colleagues compared constant rep training (8 sets of 9-12 RM) to a varied program in trained men. This was a within-subjects study design, where one leg was trained with the constant rep program, and the other leg was trained with the varied program. This means each subject is compared to himself, which helps remove any potential effects of genetic variability from the results. The constant rep program involved 4 sets of leg press and 4 sets of leg extension performed twice per week. Repetition range was 9-12 reps to failure and rest intervals were 2 minutes. In the varied program, each training session was varied among the following four different protocols:

- Varied load (8 sets of 25-30 RM)

- Varied sets (12 sets of 9-12 RM)

- Varied eccentric (8 sets of 10 eccentric contractions at 110% of the load used in the concentric sets)

- Varied rest (4 minute rest)

Given that this study did not just vary the repetition range, it technically does not fit in the criteria outlined earlier (varying only the repetition range), as only some of the training sessions varied just the repetition range. Still, this study does give us an idea of the impacts of short-term variations in training style (including repetition range), especially given the within-subjects design.

The results showed that the change in muscle size was practically identical between the conditions.

From Damas et al. (2019)

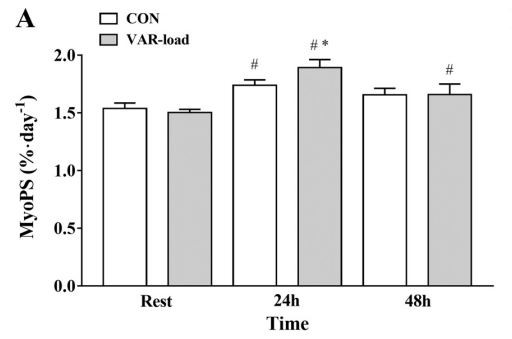

Varying the load/rep range did significantly impact muscle protein synthesis, with a higher rate of muscle protein synthesis at 24 hours in the varied rep condition. However, the difference was small.

From Damas et al. (2019)

The difference is even smaller when we look at the combined 48-hour difference in muscle protein synthesis. Such a small difference would unlikely to have any noticeable impact on muscle hypertrophy.

Total 48-hour muscle protein synthesis response from Damas et al. (2019). Note the very tiny difference between the control (8 sets of 9-12 RM) and varied load (8 sets of 25-30 RM).

One limitation of this study is that the varied group only varied rep range in some of the training sessions, so it can't give us a truly full picture of what might happen if repetition range was the only variable that was manipulated over an extended period of time. However, given the very small size of the difference in muscle protein synthesis, the lack of differences in hypertrophy observed in other studies that varied rep ranges, the lack of impact of other variations in this particular study, and the similar fiber recruitment/muscle glycogen depletion between moderate and high rep sets taken to failure, it seems unlikely that variation in the rep range between moderate and high reps will have any noticeable impact on hypertrophy.

Putting It All Together

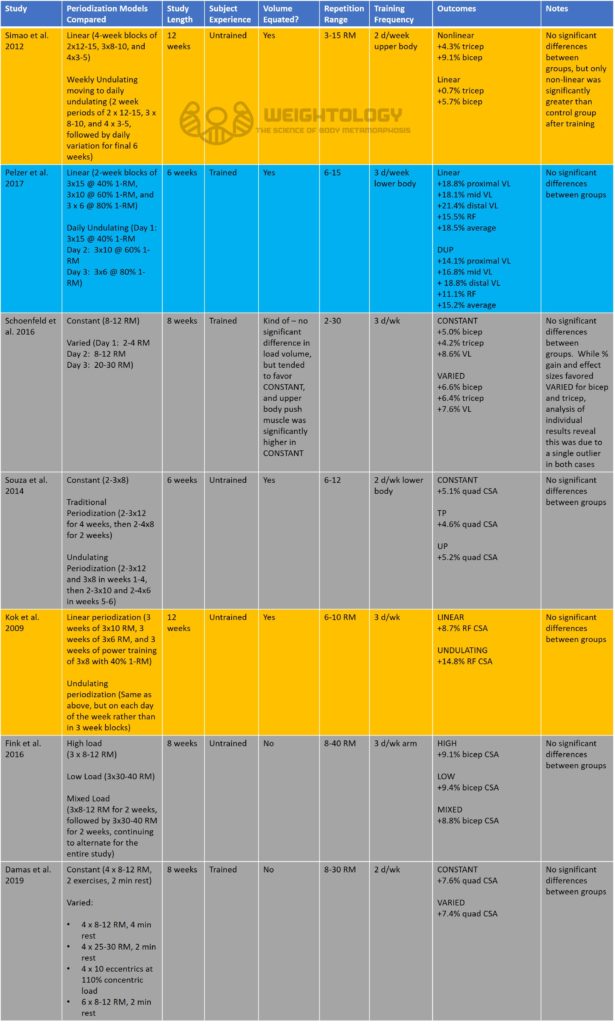

The following table summarizes the results of all these studies. Orange rows indicate studies that tended to favor frequent variation in rep ranges. Blue rows indicate studies that tended to favor block periodization/less frequent variation. Grey rows represent studies where there is no discernible difference between periodization/variation and constant rep schemes.

Looking at the overall weight of the evidence, 4 studies show no apparent benefit, one shows a slight edge to linear/block periodization over frequent variation, and 2 studies show an edge to undulating periodization over linear/block periodization. With 4 studies showing no benefit, 2 showing an edge one way, and 1 showing an edge the other, the weight of the evidence would indicate no clear hypertrophy benefit to frequent variation or periodization in your repetition ranges over more constant schemes. Now, these studies are over 6-12 week periods; it's possible that there could be a benefit over longer time frames, but if there is a benefit, the benefit is likely small.

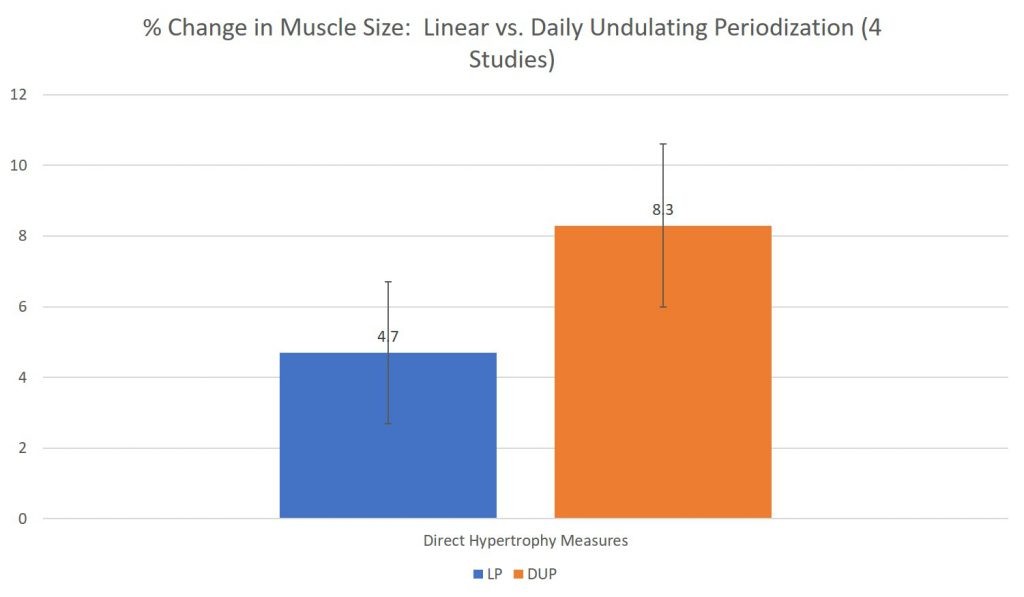

Now, this conclusion is based on one caveat...that you're training with sufficient volume to induce hypertrophy in the first place. Two of these studies tended to show inferior results for linear periodization schemes, where you can end up with extended blocks of low volume/high load training. It should be noted that these results are supported by a meta-analysis comparing muscle gains between linear and daily undulating periodization schemes, which I have reviewed here in Weightology. This meta-analysis found no significant differences in muscle gains between LP and DUP when you controlled for training volume. However, the effect size difference and confidence interval were skewed towards DUP.

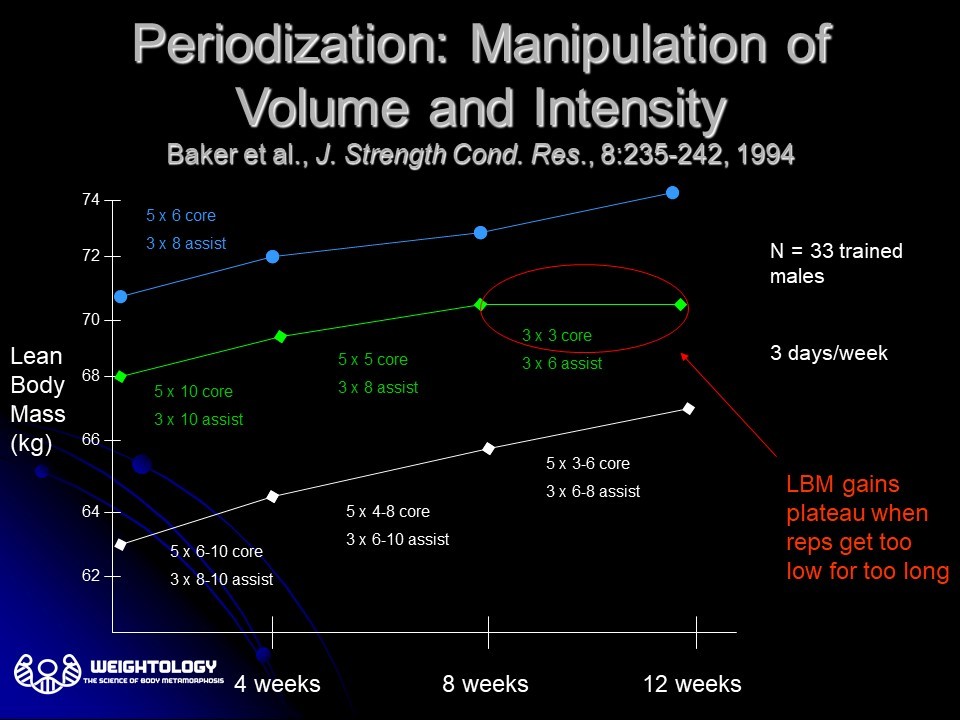

This is also similar to an older study by Baker et al. (1994), who found that, in a linear periodization model, gains in lean mass stopped when the subjects hit the low volume/high load phase of their training. This phase involved 3 sets of 3 reps on core exercises and 3 sets of 6 reps on assistance exercises. Here's a graph of the lean mass gains for the different groups in this study.

You can see how lean mass gains came to a halt when the linear periodization group hit their low volume/high load phase. This is not surprising; high load/low rep training (sets of 2-4 reps) may be inferior to moderate load training (sets of 8-12 reps) for hypertrophy if you equate the number of sets. If you do a higher number of sets of high load/low rep training so that training volume is equated, then gains in muscle are similar. However, doing a lot of sets of high load/low rep training can come at a price of sore joints and increased injury risk. Thus, if you include low rep/high load training in a hypertrophy program, it is best to include it in the context of frequent load/rep variation (like daily undulating periodization or combining the high load/low rep training with higher rep/low-to-moderate load training within a training session).

While there may not be a hypertrophy benefit to varying your rep ranges over using a constant rep range, that's not to say there are not other benefits. Incorporating high rep/low weight rep ranges in your training can give your joints a break and reduce injury risk, which, in turn, will help with maintaining your training consistency. Also, varying your repetition range can make training more psychologically interesting, which can help with motivation and reduce feelings of staleness.

Practical Application

- There is no good evidence of a benefit to periodization or variation in rep ranges for increasing muscle size over more constant rep schemes, as long as you are training with sufficient volume to maximize hypertrophy. Thus, as long as your sets are challenging (i.e., training to near failure) and volume is high enough, the rep range you use can be based on personal preference and injury risk/status.

- Prolonged periods of high load/low rep training, such as what can happen in linear periodization schemes, may not be optimal for hypertrophy. If you use high load/low rep schemes in your training, incorporate it in the context of frequent variation, like daily undulating periodization or combining high load/low reps with lower load/higher reps within a single training session.

- The benefits of rep range variation/periodization for hypertrophy likely lie in reducing joint stress/injury risk (to help with training consistency) and improving motivation through increased variation/reduced boredom.

What about this study: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28032435/

If the 5-35 repetition range shows equal hypertrophy for failure, the repetition range difference will be insignificant in this study. But despite this, the pump-training-style group improved significantly more. Why is cell swelling underrated?

This is only one study with a small sample size. Single studies will sometimes deviate from the overall body of literature.

You are absolutely right, but the interesting part is that there is no other study like this in the literature. either the rest times are the same, the weights are different, or the resting times are different, the weights are the same. Only this study used active tension focused training (heavy load long rest time) compared to pump training (low load short rest time). maybe other studies have been done but I haven’t seen it.

You are absolutely right, but the interesting part is that there is no other study like this in the literature. either the rest times are the same, the weights are different, or the resting times are different, the weights are the same. Only this study used active tension focused training (heavy load long rest time) compared to pump training (low load short rest time).

Hey, so… I dont have to “block” my training plan, and just train with for example rir2 and if my progress stops, then i should add 2 sets per week every muscle (and sometimes deload)?

Yep you don’t have the block it…just use progress as a form of autoregulation

Great article. I enjoyed reading it 🙂

great read thank you! On an exercise such as side lateral raises where eg you are working in a 10/20 rep range doing 3 sets, full rom, good form. you’ve hit 20 reps for all sets but can’t progress to a heavier weight because its too big an increase to get 10 reps plus elbow joints not great. How would you suggest progression, increase rep range to 20/30 or add in another set or something else.

Either increasing the rep range or adding more sets should work

IF I’M GETTING STRONGER WITH THE HIGH LOAD LOW REPS THEN WHEN I RETURN TO THE LOW LOAD HIGH REPS i’M SUPPOSED TO USE A HEAVIER WEIGHT SO MORE HYPERTROPHY ?

Possibly. One recent study supports that but we need more data

Hi James! The combined difference in protein synthesis observed in 48hs post-training could it be due to eccentric training? or just number of participants? Thank you!!!!!

I’m not sure I understand your question

Hi James,

What is your thought on post tetanic potentiation. I have always noticed I can lift a submaximal load more times after lifting a heavier load. Would it not seem this is the best approach to hypertrophy training. Start with a heavier load for 1 or 2 sets to facilitate greater motor unit recruitment at submaximal loads utilized thereafter. This would create varied loading/repetition ranges on all exercises in the workout. What do you think? Thanks.

Hi, Christopher, In theory, it’s not that post-tetanic potentiation would enhance motor unit recruitment (because you’ll still get max motor unit recruitment if you take a submax load to failure). Rather, if it offers a benefit, it would be due to an improvement in load volume (as you said, you can do more reps). Of course, this likely would become moot over multiple submaximal sets. I would hypothesize that it would be most useful if your overall training volume is low. My guess is, if training volume is high, it probably would not make much of a difference. It’s an… Read more »

When doing rest pause training, do the reps after the activation set technically count as low reps?

There’s no research I know of to get an idea of how reps “count” with rest-pause training. While muscle activation may be high, the overall volume is very low. For example, does 3 reps after an activation count as a full set? A partial set? We don’t know the answers to these questions. My guess is that they may only count as “partial” reps or perhaps low reps. Even though activation is high, some muscle fibers may not be getting enough time under tension as to what they may get with a “full” set.