It is no secret that, after losing weight, people have a tough time keeping it off. I mentioned in a previous issue of Weightology Weekly how only 17% of Americans are able to maintain a 10% weight loss after 1 year. Many people have repeatedly lost weight, only to regain it again and again. Even celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey struggle, despite having the money to have their own personal trainers and chefs.

We know that a change in body weight is caused by an imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure. We also know that your body tries to resist weight change and correct this energy imbalance. For example, if you eat 2000 calories per day and suddenly decrease it to 1000, you will lose weight, but you will also get hungry in the process. This hunger drives you to eat more to bring you back into energy balance. This is one of the reasons why maintaining long-term weight loss is so difficult.

However, there are two sides to the concept of energy balance. There is not only food intake, but there is energy expenditure as well. Your body can resist a negative energy balance by not only making you more hungry, but by decreasing the number of calories you burn. The extent to which this happens in humans is not clear. The challenge of successful long-term weight loss could be partly because our bodies reduce their energy expenditure to the point that it makes it very easy to regain the weight.

Energy Expenditure Primer

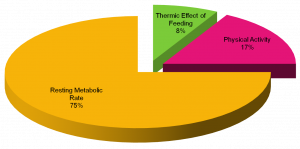

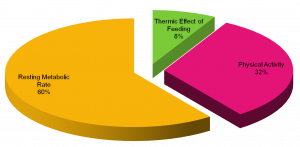

To further investigate this issue, we first need to discuss what comprises the total number of calories you burn each day. Your daily energy expenditure consists of 3 components:

- Resting Energy Expenditure (REE). Also known as resting metabolic rate or RMR, this is the number of calories you burn to maintain basic life functions at rest, such as breathing and heart rate. It is measured while lying quietly after an overnight fast. The primary drivers of REE are your internal organs; other tissues like muscle and fat contribute as well, but to a much lesser degree. REE typically makes up 60% - 75% of the total calories you burn each day, but this can go down to 50% or less in highly active people.

- Activity Energy Expenditure (AEE). This is also referred to as non-resting energy expenditure (NREE). This is the number of calories you burn due to physical activity, and this means ANY type of physical activity, which includes fidgeting, maintenance of posture, and the movement of my fingers as I type this article. AEE will typically make up 17-32% of your total daily energy expenditure, but can be higher for very active people. AEE can be divided into two components:

- Exercise. This is formal, planned exercise, such as going to the gym or going out for a jog.

- Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT). The majority of your energy expenditure comes from NEAT. This includes all activity that is not related to formal exercise, such as fidgeting or walking to your car.

- Thermic Effect of Feeding (TEF). This refers to the calories burned while digesting food. This typically makes up around 8% of your total daily energy expenditure.

Now that we know what comprises energy expenditure, we need to look at how it responds to food restriction and weight loss. In animals, food restriction and weight loss cause a decrease in REE. However, there is an increase in spontaneous activity, likely due to stimulation of food-seeking behavior in the animal. Given that food is plentiful in human society and food-seeking behavior is not necessary, we cannot apply this animal data to humans.

Research has looked at how energy expenditure is affected by weight loss in humans. We know that weight loss will decrease energy expenditure from the simple fact that you have less weight to move around. However, the question is whether the decrease in energy expenditure is proportional to the weight lost, or if it is greater than what you would expect given the weight lost. If the decrease is greater than what you would expect, then that means your body is adapting to the weight loss and trying to conserve energy. In other words, you become more efficient. In terms of organ function and REE, you expend less calories for the same function. In terms of AEE, you either move less, or you expend less calories for the same movement.

When you look at the research in humans, the data is conflicting. Some research has shown greater decreases in energy expenditure than you would expect based on weight loss alone (a phenomena known as adaptive thermogenesis), yet other studies have failed to confirm these observations. There are many possible sources of error in these studies that may contribute to the conflicting results. For example, some of the studies that have looked at this problem have used the doubly-labeled water technique to measure energy expenditure in free living people. These studies assumed the person was weight stable. However, if the person is very slowly gaining weight, then an abnormally low energy expenditure will not be detected. For example, let's say I have a truly weight stable, 200 pound person (person A) with an energy expenditure of 3000 calories per day. Let's also say that this person has never had a weight problem. Because this person is weight stable, I know that he needs 3000 calories per day to maintain his weight. Now I take another 200 pound person (person B) who used to be 250 pounds. I think he is weight stable, and his energy expenditure is also 3000 calories per day. I compare him to person A. Since they are both expending 3000 calories per day, I assume that person B's energy expenditure is normal for his body weight. I then infer that person B needs to eat 3000 calories per day to maintain his weight. However, let's say that person B is slowly gaining weight and I don't know it. This means that person B needs to eat less than 3000 calories to maintain his weight (let's say 2800). If person A needs to eat 3000 to maintain his weight, but person B only needs 2800, then person B will be more energy efficient. However, I will fail to detect this because I assumed that person B was weight stable.

An Elegant Study

To get a better handle on how long-term weight loss will impact energy expenditure, and whether adaptive thermogenesis occurs in humans, Rudolph Leibel, a well-known researcher in metabolism and weight loss, and his colleagues performed a study on people who had lost at least 10% of their weight and kept it off for more than a year. The researchers examined 7 trios of subjects. Each trio consisted of the following:

- A subject who was at his/her usual weight

- A subject who lost at least 10% of his/her weight, and had maintained it for the last 5-8 weeks

- A subject who lost at least 10% of his/her weight, and maintained the loss for at least a year

The subjects were matched for sex, meaning that each trio would contain all males or all females. They were also matched for weight, meaning that the subjects in a particular trio had similar body weights. The subjects lived in the clinical research center throughout the study. They were fed only a liquid formula diet, which contained 40% fat, 45% carbohydrate, and 15% protein. Their caloric intake was adjusted until weight stability was achieved. A stable weight was defined as a daily weight fluctuation of less than 10 grams for at least 2 weeks. The formula diet was important, as a mixed food diet can cause random shifts in weight due to shifts in salt and carbohydrate intake (which is another limitation of previous research in this area). Thus, diet and weight were precisely controlled. Since weight was stable, 24-hour energy expenditure had to match 24-hour energy intake. Thus, the subjects' calorie intake would also indicate the number of calories they were burning each day. REE was measured under a metabolic hood. TEF was measured by feeding the subjects when they were under the hood, and measuring the increase in metabolic rate. AEE was calculated by subtracting REE and TEF from total daily energy expenditure. Body composition was measured using hydrostatic weighing.

The researchers then took 83 subjects at their initial weight, and developed regression equations that related energy expenditure to age, fat-free mass, and fat-mass. The observed energy expenditures for the trios were then compared to what these equations predicted their energy expenditures should be.

Adaptive Thermogenesis: A Reality

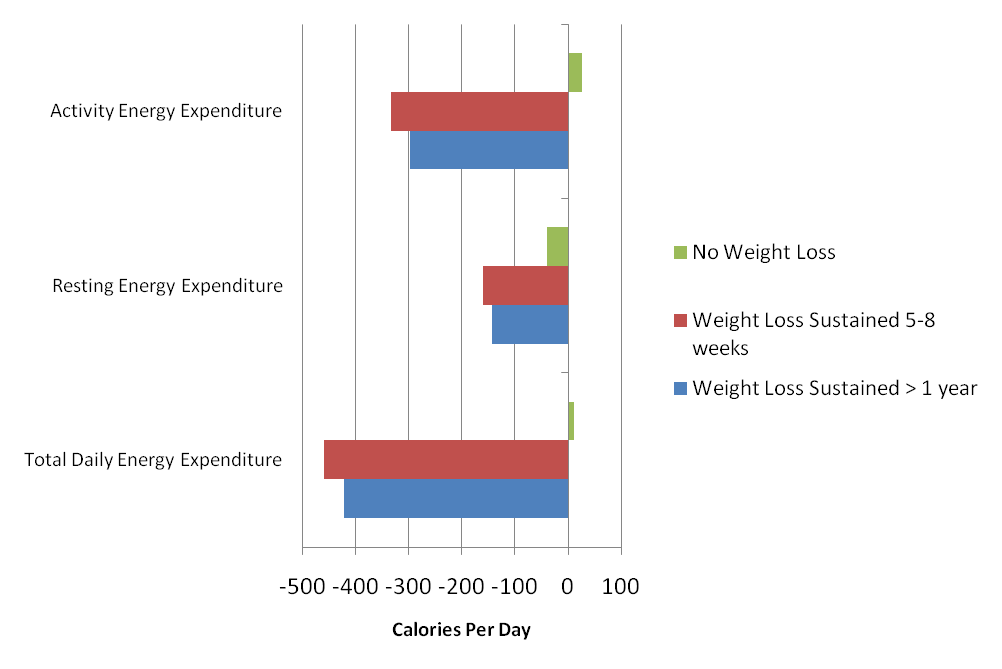

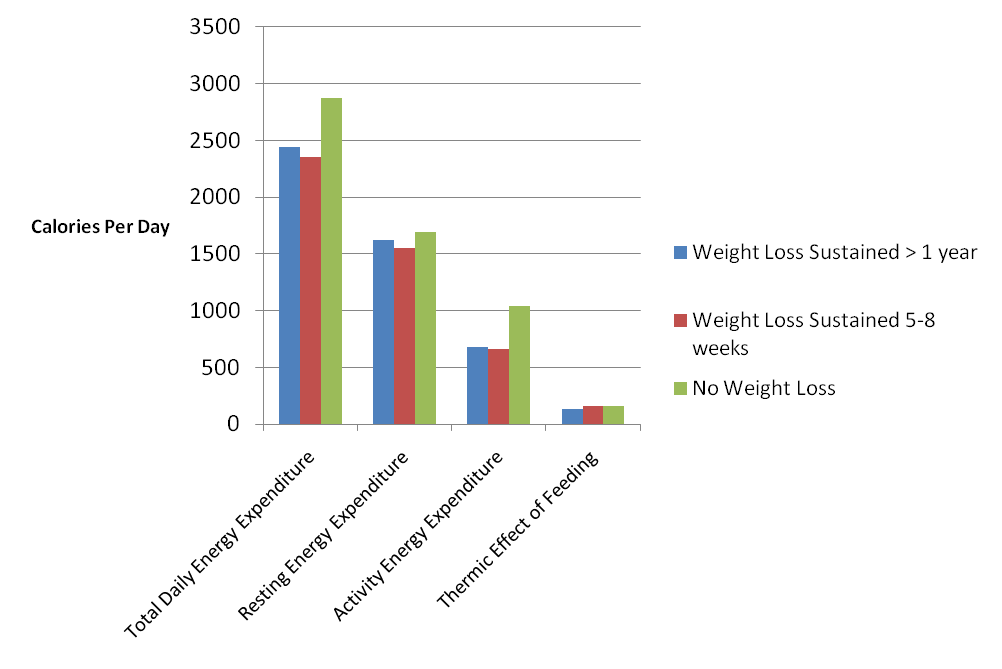

The following chart shows the average energy expenditures of the subjects:

You can see that the resting metabolic rate of the subjects who lost weight were slightly lower than the subjects who had never lost weight, despite the fact the subjects were of similar weight. The difference amounted to 72 - 139 calories per day. The difference in activity energy expenditure was much more dramatic, coming in at 366 - 383 calories per day. These differences in resting metabolic rate and activity energy expenditure led to a difference in total daily energy expenditure of 428 - 514 calories per day. TEF was not affected by weight loss.

When the observed energy expenditures were compared to the values predicted by the equations, the results were similar:

Differences between observed energy expenditures and the predicted energy expenditures for subjects who lost weight and who didn't lose weight. You can see that the energy expenditures for the subjects who lost weight were lower than you would predict, but the energy expenditures for the subjects who had never lost weight were very close to what you would predict. This indicates adaptive thermogenesis with long-term weight loss.

You can see that the energy expenditure values were lower than predicted for the subjects that lost weight, but were similar to predicted for the weight-matched subjects that had never lost weight. For REE, values were 143 to 161 calories lower than predicted in the subjects who had lost weight. This indicated a slight lowering of metabolic rate that is sustained even when the weight loss is maintained for more than a year. Where weight loss had the biggest impact was on activity energy expenditure, with values being 298 to 334 calories lower than predicted. Total energy expenditure was 422 to 460 calories lower than predicted in the weight loss subjects.

A NEAT, Efficient Explanation

It is clear from this study that metabolism (in terms of resting metabolic rate) slows with weight loss, and this decrease is greater than you would expect with the amount of weight lost. This decrease is present even when someone has maintained weight loss for more than a year. However, the slowdown of metabolic rate is not the primary culprit for why it's so easy to regain weight, as the slowdown in metabolic rate only amounts to around 150 calories per day.

The main reason why we have a greater-than-expected decrease in energy expenditure with weight loss is because we become less active. This doesn't mean we exercise less, either, as exercise is a conscious choice. It means we unconsciously reduce our NEAT and spontaneous activity. It also means we become more efficient in the activity we do; we expend less calories for the same movement. In fact, 35% of the decrease in activity energy expenditure can be attributed to an increase in efficiency. Overall, we move around less, and we become more efficient at the movements we perform. Combined with a decrease in resting metabolic rate, we end up burning over 400 calories per day less than you would expect for someone of our same height, weight, gender, and body composition. This is not only why weight loss eventually plateaus, but also why weight is so easily regained.

Other research has verified that NEAT and physical activity decrease with weight loss, and that they are the primary drivers behind why energy expenditure decreases more than you would expect. In one study, obese subjects lost 23.2% of their body weight. Total daily energy expenditure was 75.7% of what you would predict, and nearly all of the energy savings were due to a decrease in activity rather than a decrease in metabolism. In fact, the decrease in activity amounted to 582 calories per day!

It has also been found that changes in activity predict the amount of weight gained over time. In one study, women were followed for a year. They were divided into maintainers (a weight gain of less than 3%) and gainers (a weight gain of more than 10%). Changes in activity energy expenditure explained 77% of the greater weight gain in the gainers.

High Physical Activity Levels Prevent Weight Regain

The good news is that, since the reductions in energy expenditure are primarily due to decreases in activity, one can make conscious choices to increase physical activity to a sufficient extent to prevent weight regain. Research has demonstrated that high physical activity levels can help with maintenance of weight loss. In one study, subjects who exercised enough to expend 1000 calories per week regained most of their weight, but subjects who expended 2500 calories per week maintained most of their weight loss. Similar results have been observed in other studies. Subjects in the National Weight Control Registry, a database of individuals who have maintained at least a 30 pound weight loss for over a year, expend an average of 2620 calories per week in physical activity.

Remember that physical activity doesn't have to include formal exercise. NEAT makes up the majority of your activity energy expenditure, and thus has the greatest ability to impact it. In fact, walking at only 1 mile per hour will double your energy expenditure over sitting. Thus, anything that you can do to accumulate physical activity throughout the day will dramatically improve your chances of maintaining weight loss over the long haul. Even small things, like parking a car further away from a destination, or taking stairs rather than an elevator, can add up if accumulated throughout the day. But because activity can decrease on an almost unconscious level, you need to make a deliberate conscious effort to get as much activity as possible in throughout your day, every day.

Hi James,

I found this to be very informative but I was somewhat confused by this article.

Are you saying that people who lose weight, actually become less active than prior to losing weight?

Why? I’m not sure I understand?

Can we control our NEAT?

Also, if we lose weight but not muscle, (or if we work to rebuild it), can we not have such a large reduction in calories?

Sorry for the late question.

If you could help out, that would be great, I have found very few answers that I need on the net and even through nutritionists/doctor.

Hi, Vanessa,

Yes, I am saying that people who lose weight become less active than prior to losing weight. The mechanisms are still not completely understood by researchers. Yes, you can control NEAT, but the research indicates you need to make a conscious effort to do so; otherwise, you will unconciously become less active. Building muscle will not stop this, as the decrease in NEAT has nothing to do with muscle mass.

Hi James,

I found this to be very informative but I was somewhat confused by this article.

Are you saying that people who lose weight, actually become less active than prior to losing weight?

Why? I’m not sure I understand?

Can we control our NEAT?

Also, if we lose weight but not muscle, (or if we work to rebuild it), can we not have such a large reduction in calories?

Sorry for the late question.

To what extent can the reduction in calories burnt be explained by a reduction in muscle fibre?

Hi, Chris,

It would not be due to a reduction in muscle fiber. The researchers will often express the RMR in relation to lean body mass and they still find a reduction. Plus, muscle does not contribute much to resting metabolic rate (only 6 calories per pound of muscle).

Hi, I know I’m kind of late for this article!

I was just wondering if going from about 200 lbs and a fat percentage of around 19 – 20, down to about 176 – 180 lbs and a fat percentage of 10 – 12 would result in the same decrease in metabolism? I never considered myself “overweight”, but when I started to lose ab-definition I figured I wanted to lose some weight.

I hope that going up to 200 lbs did not ruin my metabolism 🙁

I have been surprised that having been overweight since birth – that now I have gone from 210lbs to 165lbs (yo-yoing in between), I am naturally more active just in day to day life, so as I eat more on maintenance, (now 2000cals/ day as opposed to 1500 cals when dieting), I am not gaining. High intensity exercise is overrated – most can’t maintain it, just keeping off the couch is the answer.

Easily said than done! You forgot to factor in the ache and pains associated with age. This may be the biggest factor why overweight people became overweight in the first place…tired, aching body. And when they try to lose weight, they regain them for 2 reasons: 1.) They can’t have so much energy expenditures because of tred aching body 2.) They are in celebratory mode that they have successfully lost weight, and that it could be done. They celebrate with food they’ve missed…Problem is the celebratory mode feels better than the dieting mode. So they get fat and regain their… Read more »

James would I be right in assuming that that high amount of exercise wouldn’t HAVE to be done if calorie intake was monitored just as much as it was when dieting down?

I also couldn’t guarantee to do that amount of exercise either (I know, bad!) however, I don’t see why long term weight maintenance can’t be achieved by still watching the calories??

It may help people like the above poster was referring to.

You are correct that a high amount of exercise would not have to be done if you had very strict control of your calorie intake. Unfortunately, it is very difficult for most people to adhere strictly to low calorie intakes for extended periods of time, which is why high volumes of exercise become a necessity for many.

Thanks for the reply James.

When you say difficult for most, are you referring mainly to keeping track of calories on a daily basis?(basically forever)

Like I said above, I am not so sure I could guarantee to do that amount of exercise but I feel quite confident that I could keep up with watching the calories. Knowing that that would be an option as well is reassuring.

Thanks again.

Just stumbled upon this great article. Very enlightening. It’s very difficult for me, at 48, to get that amount of exercise now. To burn 400 calories now requires a solid hour of heart pumping step aerobics with weight training added in circuits. I used to be able to do it five days a week. I can’t anymore. Between the calf microtears, the iliotibial band syndrome, and the arthritic knees, my body can no longer sustain that level of physical activity. Not to mention that I’m just plain tired the older I get. I’ve had to bring my exercise down to… Read more »

Am 59 and lost 45lbs 6 months ago. Lifestyle is the key – biking easier on the knees. Have found am more active on the NEAT level, simply because I’m not carrying around 45lbs of fat – getting the blood moving around my brain makes me feel younger AND able to catch the ‘activists’ (Grandchildren). On about 2000cals/day.

James,

For someone losing a lesser amount of weight, (going from 10% BF to 6% BF) do you think the reductions in NEAT would be proportionally smaller? I’ve had some clients plateau at fairly low calorie levels, and I’m guessing there’s a rapid decrease in NEAT under a certain threshold.

Excellent article and I’m looking forward to your book.

-Armi

Armi, Yes, the reduction in NEAT would be proportionally smaller. Remember that NEAT will always decrease with fat loss since you have less weight to move around. However, the research also shows that the decrease in NEAT is greater than you would anticipate based on the weight change alone. I don’t know of any research that has looked at whether there are thresholds for greater drops. For example, does NEAT decrease more rapidly when someone goes from 10% to 6% body fat (essentially losing 40% of their body fat), versus someone going from 25% to 15% (also a 40% reduction)?… Read more »

That would be an interesting study. I find NEAT extremely fascinating, and it seems to fill a lot of holes in the research on energy balance.

Here’s another thought:

I know high protein diets don’t produce greater weight loss in the long term, despite what might be expected from the higher thermic effect of food. Do you think a reduction in NEAT might be one of the compensatory mechanisms by which this effect is rendered null?

thanks again 🙂

I don’t think the reduction in NEAT is a compensatory mechanism regarding high protein diets. I think it’s more simply an issue of adherence and “calorie creep.” Over time, people just become more lax about their dietary intake.

That makes good sense. Thanks James.

Hi James, this is really a very illustrated experiment. I loved it! I think that, without changing our habits we could take care a little better of our weight. For example, taking the stairs instead of the elevator, or walking instead of taking the bus, or not eating carbohydrates after 6-7 pm, also drink a lot of water… Following this simple rules you can, not loose weigh, but maybe maintain what you have. That’s what I do!!

This is very interesting and explains a lot of my own observations. I lost 90 pounds about 5 years ago. While losing the weight (on the UCLA RFO program – 920 calorie “fast” and lots of exercise) I could predict my weight loss each week within a tenth of a pound. I used a polar heart rate monitor to estimate calories out, and traditional BMR tables. Over the past 5 years and a massive exercise program I have increased my muscle mass by nearly 40 pounds (bicep from 12 to 16.5; chest from 40 to 46; etc.) and cardio 4… Read more »

Wonderful article; really been enjoying your blog – nice to have another good science fitness blog. The article highlights what I’ve been constantly afraid of, ever since I lost a significant amount of weight (60 pounds). Even with consistent exercise/lifting, I find that the only way I can stay in a lean state is with the help of ephedrine and caffeine.

Jon, I used to do the EC stack too (I’ve lost and maintained a 120+ pound loss), but I think it was more of a psychological dependency on this fat burning stack. Once I stopped taking them, I just had to figure out how much exercise I needed to do and how much I could eat to stay at a certain size. The best maintenance technique for me over the years (I’ve been around the same size for @ 5 years now) was a simple pair of size 36 jeans. I hate wearing tight pants, so once they started to… Read more »

Awesome comment and I’d like to add that the same is true for me. The EC stack was very helpful to me when I was losing weight, but I decided I didn’t want to be on pills forever. I agree that after a certain point, for me, it became more of a psychological aid than anything else. I still drink coffee (Seattle native here!) but no more pills for me and I haven’t noticed any change since I stopped. (Tapered off over a period of two weeks and experienced a mild fatigue/tiredness but that ended quickly.) We have to always… Read more »

Thanks, Jon, glad you liked the article!

Used you with a reference and link. Do you know the calorie ranges that people maintained on? The “never lost weight” group ate an average of 2700ish calories a day. And the “maintaining for a year” group ate an average of 2400ish calories a day. That is still a good number of calories. The average women in the National Weight Control Reg reports that she is maintaining on 1350 calories a day, or something ridiculous like that. Granted, no ONE person is “average”… but an average of 2400 calories a day looks pretty good to me! And is WAY better… Read more »

Denise,

The calories ranged from 1700 to 3600. Only 4 of the subjects had maintenance intakes of less than 2000 calories per day.

Anyone who claims that they are maintaining on 1350 calories per day is underreporting. There are studies showing that, when you take people who report these low calorie amounts, and actually provide them with the calories they claim to be eating, they lose weight.

Thanks and COOOOL!

By any chance, do you have any references for these studies available? I’d love to take a look at them.

The references are embedded in the hyperlinks. When you click on the hyperlink, it will take you to the PubMed abstract.