A recent study out of Princeton University has the high-fructose corn syrup alarmists out in full force. This study compared the effects of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) to regular table sugar (sucrose), looking at their effects on body weight, body fat, and triglycerides (fats that float around in your blood). The study found that the rats fed HFCS gained more weight and abdominal fat than the rats fed sucrose. This study has strengthened the belief of some people that HFCS is contributing to obesity in our society, and that it is worse than regular sugar. But is it really?

To answer this question, we need to take a close look at this study. The researchers performed 2 experiments. In the first experiment, male rats were divided into 4 groups. Group 1 (the control group) was fed a regular diet. Group 2 was fed the same diet, with the addition of 24-hour access to water sweetened with HFCS. Group 3 had the regular diet with 12-hour access to the HFCS-sweetened water. Group 4 had the regular diet, with 12-hour access to sucrose-sweetened water. The rats were tracked for 8 weeks; weight was measured, along with food, sucrose, and HFCS intake.

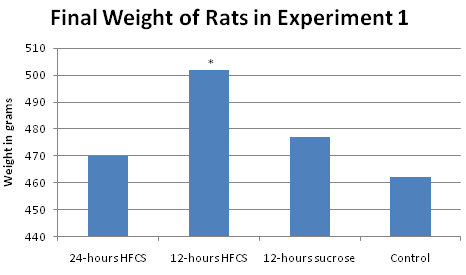

You can see the results for experiment 1 in the following chart:

The rats who got HFCS for 12 hours gained significantly more weight than the other 3 groups. At first glance, this would make you believe that HFCS makes you gain more weight than sucrose, even if you are eating the same number of calories. However, there is a problem with these results. Take a look again at the chart above. If the rats fed HFCS for 12 hours gained more weight, why didn’t the rats fed HFCS for 24 hours also gain more weight? They got HFCS for a full 12 hours more, yet didn’t gain more weight. This is a glaring inconsistency in the results…an inconsistency that the researchers never tried to explain.

Rather than some unique effect of HFCS, a more likely explanation is one of chance. Put on your math hat, because we need to talk about some statistics. Researchers use statistics to get an idea of the probability that their results are due to chance. When the scientists run their stats, they get what is known as a P value. The P value tells you the probability that the results are not due to chance. Usually, if the P value is less than 0.05, a scientist will call the results “significant.” In other words, if you did the experiment 100 times, you would only see these results less than 5 times if there wasn’t a true effect.

The above only holds true if you’re doing a single comparison. If you start comparing a bunch of groups all to each other, the probability of a fluke result dramatically increases. The Princeton study is a perfect example. There are 4 groups all being compared to each other. That makes for 6 total comparisons (group 1 to group 2, 1 to 3, 1 to 4, 2 to 3, 2 to 4, and 3 to 4). Each one of these comparisons is being tested against that 5% level. To calculate the probability of a fluke result in this case, we calculate 1 – (0.95x0.95x0.95x0.95x0.95x0.95) = 26%. In other words, there is a 1 in 4 chance that the greater weight gain in the HFCS-fed rats is a fluke. I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t put too much faith in results that have a 1 in 4 chance of being wrong. There are ways that scientists can adjust for this, but the Princeton researchers didn’t appear to make those adjustments. Thus, it is not surprising that there was a significant result observed in 1 out of the 4 groups…you would expect this to happen based on random chance alone.

In Experiment 2, the researchers divided male rats into 3 groups: 12-hour HFCS, 24-hour HFCS, and control. They tracked the rats for 6 months. Both HFCS-fed groups gained more weight and fat than the control, and also had higher triglycerides. However, the researchers didn’t compare HFCS to sucrose in this group, so this experiment doesn’t’ say anything about whether HFCS is any worse than sucrose. The researchers also didn’t say anything about food intake and whether the HFCS-fed rats ate more than the control rats.

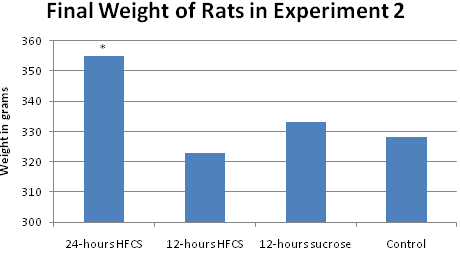

Experiment 2 also featured female rats on one of the 4 diets used in Experiment 1. These rats were tracked for 7 months. The following chart shows the results of the experiment:

The female rats fed HFCS for 24 hours a day gained significantly more weight than the other groups. Now compare these results to the chart for Experiment 1 earlier. Do you see the disparity? In Experiment 1, the rats fed HFCS for 12 hours per day gained the most weight. However, in Experiment 2, the rats fed HFCS for 24 hours per day gained the most weight, and the female rats fed HFCS for 12 hours didn’t gain any more weight than the other groups. Why did the 12-hour group gain the most weight in one experiment, but the 24-hour group gain the most weight in a nearly identical experiment? This is a glaring contradiction in the results, and a problem which the researchers did not discuss. We also have the same statistical problem that we did with Experiment 1. Since there are 6 comparisons, there is a 1 in 4 chance that the results are wrong (and ironically, we have 1 out of the 4 groups showing a significant result). In fact, when we take both experiments combined, we have at least a 50% chance that the results of one of the experiments are wrong. Out of all the comparisons being made, we would expect to see a couple groups show a significant result based on random chance…and that’s exactly what happened in this study.

The bottom line is that there is no valid reason for HFCS to be any different than sucrose in the way that it affects your body. They are both nearly identical in their composition, containing roughly half fructose and half glucose. They are both nearly identical in the way they are metabolized by your body. There is no practical difference between the two as far as your body is concerned. Now, I’m not saying that you should go out and consume all the HFCS that you want. The point is that there is nothing uniquely “bad” about HFCS compared to regular sugar. HFCS is not uniquely responsible for weight gain as some people would have you believe.

If you see a product with HFCS and a similar product with natural table sugar, don’t assume the product with natural sugar is any better. Rather than worrying about whether something contains HFCS, you should strive to reduce your intake of all types of added sugar and refined carbohydrates in your diet. It is much more important to look at the big picture; keep your physical activity high, manage your overall food intake, make sure most of your food is from minimally refined sources, and keep your protein intake high. This is what will help you lose weight and keep it off, rather than singling out HFCS in your diet. Don’t let the fructose fear-mongerers fool you.

Hi James, The study below indicates a possible reason why HFCS might be more fattening – some of it may have much higher levels of carbohydrate (thus calories) than labels claim. Dr. Ray Peat sent this to me. What do you think? * FASEB Journal 2010 PN Wahjudi Carbohydrate Analysis of High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS) Containing Commercial Beverages Paulin Nadi Wahjudi1, Emmelyn Hsieh1, Mary E Patterson2, Catherine S Mao2 and WN Paul Lee1,2 1 Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute, Torrance, CA 2 Pediatric, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA The carbohydrate analysis of HFCS is based on methods which first… Read more »

Lillea,

You could be on to something here. Thanks for bringing this to my attention. I’ll try to review this article in a future issue of Weightology Weekly.

James and Lillea, The full study is not yet available, so making any definitive comment on its validity is not possible. However, I think it is important to recognize that this is simply an abstract at this point, has not been published in a peer –review journal, and therefore has not passed the scrutiny of trained scientists, with no vested interest in the subject, whose views would be needed for an objective assessment of the adequacy of the experimental design and the validity of the conclusions. Manufacturers of HFCS do not use acid hydrolysis and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS in… Read more »

Good old Fisher developed the use of P values for statistical inference, mainly for agricultural research. It is said that he himself supported the the notion of adopting a value of P=2.5% as providing an inference of “not due to chance”. In my own personal decision making I pay no attention to results which do not reach a level of P=1% – but then I also ignore results have Risk Ratios less than 500% or Numbers to Treat less than 15. I have a view that I should be persuaded that my current practice should change – so I prefer… Read more »

@Daniel … I watched “King Corn,” it was an interesting documentary. I didn’t get any evidence from it that HFCS was bad or unhealthy, simply that it is in a lot more foods than we think. It is a valid point that people wanting to watch their intake of sugars will have to read labels very carefully, but that’s always been the case. “Chemicals destroy the brain and body but cause cancer” … you’d have to state which chemicals specifically, and how they destroy what. Note there are chemicals that we use to treat diseases and help people with brain… Read more »

its clear so damn clear that that chemicals not only destroy the brain and body but cause cancer and so many other diseases high fructose corn syrup is a chemical people, not natural the ingredient they use to make it has a (skull and bone sign) watch king corn and do some research on it

Daniel,

In addition to what Paul already said, your assumption that “natural” is somehow better is not based on scientific evidence. Please read my blog post here where I discuss artificial versus natural ingredients.

All substances are “chemicals”…even natural ones.

“Since there are 6 comparisons, there is a 1 in 4 chance that the results are wrong (and ironically, we have 1 out of the 4 groups showing a significant result)” You should learn the meaning of the word “irony” before using it. Right now, even Alanis Morissette could teach you a thing or two about the word “irony.” There can be no irony when the outcome EXACTLY meets your expectations, as is the case with this study. I’ll give you an example of proper usage: “It is ironic that the biggest defenders of HFCS (James Krieger and Alan Aragon)… Read more »

@vic

No, I’d say the big picture is being logical. The results in this paper clearly do not indicate HFCS as being worse than sucrose. You’ve provided nothing of substance against that claim, only commenting on irrelevant diction.

I haven’t reviewed the literature well on this topic…James, aren’t there any papers with well controlled methods that show some downside of HFCS vs sucrose?

The way I have interpreted his article is that he is saying that it is no worse for you than sugar as it is pretty much identical in the way it is processed and it’s molecular structure. He is also emphasising that one shouldn’t eat it in abundance, but then again, I don’t think anyone would advise you to eat sugar in abundance, so in this respect he is treating them as being equal. I’ve no idea if Mr Krieger and Mr Aragon have some ulterior motive for publicly branding HFCS as being of equal value to sucrose, be it… Read more »

Good article. For further reasons why this study shows crap, read Alan Aragon’s april research review for an article about rats and how their carbohydrate metabolism differs from humans.

Thanks for the comment, Josh. Yes, there are distinct differences between rodents and humans in regards to fat & carbohydrate metabolism, which means they aren’t always the best models for looking at these things. Glad to hear that Alan covered this in his research review.

I’m sorry, but much of what you state about p-values here is incorrect – for example, “The P value tells you the probability that the results are not due to chance” is wrong – and you’re using a p of 0.05 when the study only says that p < 0.05. Their p value could easily have been 0.00001.

Hi, Kevin, “The P value tells you the probability that the results are not due to chance” is wrong The P value is the probability of obtaining a test statistic at least as extreme as the one that was observed, assuming the null hypothesis is true. It tells us the chance that a experiment of a “null effect” gives us such a result. In this case, it tells us the chance that we would see a greater weight gain in the HFCS-fed rats, if HFCS has no such effect. In other words, if I were to do 100 identical experiments,… Read more »

Great article, James.

I will echo Julie’s post – I love the way your break the math and science down into something easily digestible for us layfolk. You don’t dumb it down – you make it accessible.

I have been reading your stuff on the BS Detective for some time now, and will happily follow along with you here.

Thanks for the compliment, Cord! Glad you like the site

James,

You might also want to review and comment on Dr. Lustig’s commentary about HFCS. His position is contrary to what you state. Since over 400,000 have viewed this video – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBnniua6-oM – it might be worth a critical review on your part.

On my end, I try to avoid all processed sugars.

Looking forward to reading your blogs.

Ken Leebow

http://www.FeedYourHeadDiet.com

Hi, Ken,

Thanks for your comment. Alan Aragon has written a very good critique of Dr. Lustig’s lecture.

James

You label Lustig as a High Fructose alarmist by linking to Aragon’s critique in your lede. The fact is that Lustig is very clear that HFCS and sucrose are metabolically equal. He says so a number of times in his famous lecture and it should be underlined by the fact that he references the work of John Yudkin’s published in 1972 as the precursor to his own work. Yudkin’s laid out the problems with sugar before the industrial adoption of HFCS. Because HFCS brought down the cost of sweetening, the fact that it’s adoption tracks with the obesity epidemic and… Read more »

HFCS is also nearly half glucose and half fructose. There can be more variation in HFCS than sucrose but its within 2 – 4% So its nearly equivalent to sucrose in proportion.

The most common formulation of HFCS is 55% fructose while sucrose is 50%. It seems to me the difference computes to 10%. Besides that some studies indicate that the ratio is often varied by beverage companies so that a higher ratio in favor of fructose over glucose is used. This is a very significant difference, especially over a long period of time.

WOW this was very interesting. Nice that someone finally was honest about how research is swayed to the highest bidder. The best part about the article is that it was very easy for the average person to read. Thanks and keep them coming.

Hi, Julie, thanks for commenting! I’m happy to hear that the article was easy to read and understandable.