Many people use meal replacement (MRP) shakes or powders to help them lose weight and get lean. They are convenient, quick, and easy ways to help increase your protein intake and reduce your calorie intake. The research also demonstrates that they are effective tools for weight and fat loss. We often like to think that one of the ways they help is because of the high protein content. We know that a diet high in protein helps suppress appetite and reduce calorie intake. Thus, it stands to reason that a high protein MRP shake or powder would have a similar effect. However, some research suggests that may not be the case. MRP shakes and powders are generally ingested in a liquid form, and liquid calories are not as satiating as solid-food calories, even if high in protein.

Another possibility as to why MRP shakes and powders help may have nothing to do with the protein content. Instead, it may be purely behavioral. Similar to the effect of portion size, the amount of food offered as a meal replacement may be accepted as the "norm" for the meal. Thus, as long as there is no compensatory increase in appetite and food intake when you use a MRP, you will establish an energy deficit and lose weight. Researchers at Cornell University investigated whether the controlled portion sizes, rather than macronutrient content, of MRP's played a role in calorie reduction.

The Study

Seventeen subjects (10 females and 7 males) completed the study. They were an average age of 24.8 years, and their mean body mass index (BMI) was 21.2. Thus, these were normal weight subjects on average. The subjects were randomly allocated to one of two groups. The groups differed only in the order they received the treatments. During week 1 (Monday through Friday), the subjects ate all of their meals and snacks ad libitum (meaning they ate as much as they felt like eating). All of these meals and snacks were prepared by the research lab. The subjects recorded everything they ate on the weekend and were asked to maintain that same intake for the next 4 weekends.

In week 2 and week 3, subjects in Group 1 were allowed to choose and eat one of the following commercially available foods in place of the ad libitum lunch:

- Chef Boyardee Pasta

- Smucker's Uncrustables

- Kashi Bar

- Lean Pocket

- Campbell's Soup in Hand

The average calorie content of these foods was 200 calories. The foods contained an average of 7.2 grams of protein, 26.4 grams of carbohydrate, and 6.9 grams of fat. In addition, participants could select to each a fresh apple, which was about 50 calories.

During these same 2 weeks, Group 2 continued to eat ad libitum during lunch. Then, for weeks 4 and 5, Group 1 returned back to eating ad libitum lunches, while Group 2 chose and ate one of the meal replacement lunches.

All food and drinks were prepared by the research lab during the weekdays. The researchers told the subjects that they were interested in their food intake and to eat as much or as little as they desired. They were instructed to not eat any food during the study that was not prepared by the staff. On occasions where subjects could not eat at the lab, more than enough of the food that would be served at the ad libitum meal was assembled, weighed, and packaged for them. Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) were used to assess hunger and fullness before and after each meal.

The Results

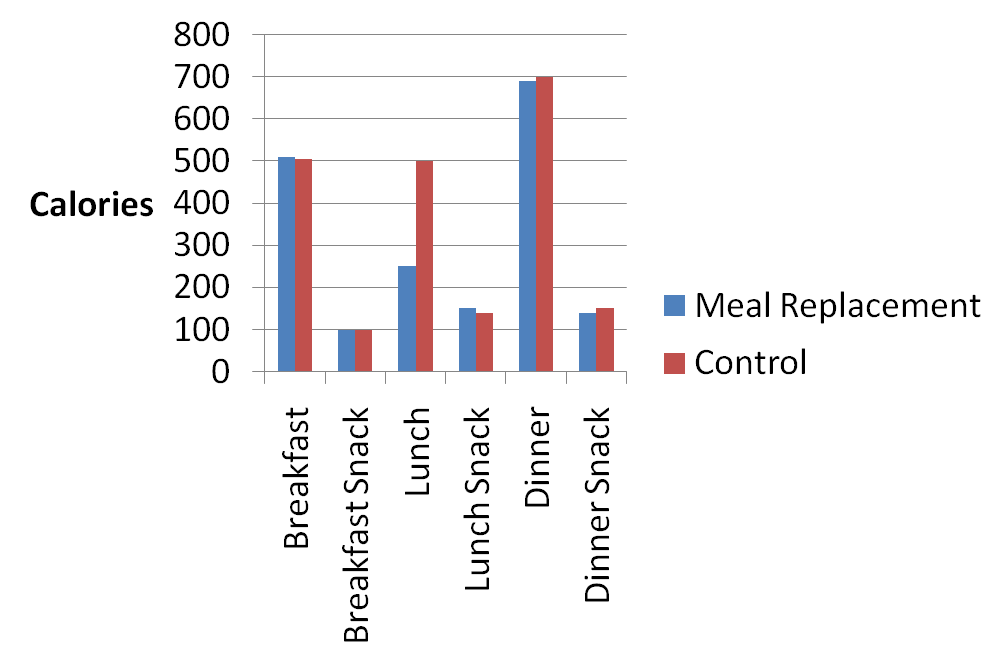

There were no differences between Groups 1 and 2 in terms of food intake. Thus, the researchers combined the data for groups 1 and 2. When looking at the subjects' calorie intakes across all meals and snacks during the day, calorie intake was about 250 calories lower at lunch when the subjects consumed the meal replacements, compared to an ad libitum lunch.

As you can see, the subjects did not compensate for the lower calories at lunch when they consumed the MRP's. This held true over 2 weeks, so there was no compensation even 14 days later. Total calorie intake was significantly reduced from 2,057 calories to 1,812 calories when the MRP's were used. There were also no significant differences in hunger and fullness ratings when comparing the ad libitum lunch to the MRP's; this is despite the fact that calorie intake from the MRP was half that of the ad libitum lunch. No differences were observed between the types of MRP's.

The use of the MRP's also caused an energy deficit, resulting in about a 1 pound weight loss over 2 weeks, compared to no weight change with the ad libitum lunch.

A Good Start, But Serious Limitations

To my knowledge, this study is the first to examine the mechanism behind how MRP's help with weight and fat loss. The results certainly suggest that the controlled portion sizes are a key factor, especially since none of these foods were high in protein or fiber and that there were no differences in ratings of appetite or fullness between the ad libitum lunch and the MRP's. Also, because these foods are packaged so that the entire package is one serving, there is no "portion distortion" or unrealistic psychological expectations as to what makes for a normal portion. The person buys a 200 calorie package of the food, and knows that this is a normal portion size for this particular food. Reductions in portion sizes have been found to be effective for reducing calories; in one study, people consumed 250 calories less per day when they consumed 75% of their normal portions.

There are some glaring limitations to this study of which you should be aware:

- This study does not rule out the possibility that MRP shakes and powders help due to a high protein content, because no MRP shakes were used in this study. In fact, some people would not consider the foods used in this study as MRP's. The Kashi bar was the only thing closely resembling what some people tend to use as MRP's. The foods in this study are often more considered "grab and go" type foods.

- Similar to #1, this study does not rule out the effect of macronutrient content of MRP's. This is because all of the MRP's in this study had similar macronutrient contents. This study design would have been much stronger if some MRP's of varying macronutrient contents had been included, particularly a high protein MRP.

- Since the study was done in a controlled lab setting, the subjects may have altered their normal eating behavior. Results could have been different in a more free-living situation. Unfortunately the limitation of a more free-living situation would mean that the researchers are less able to monitor the food intake of the subjects. Nevertheless, the lack of weight change by the subjects during the ad libitum feeding suggests that they were eating normally.

- The subjects were mainly normal weight, college-aged students. Since they are young, their bodies may be better at regulating calorie intake versus someone who is older (see this research review which suggests how age can affect appetite regulation). Also, the fact that they are normal weight indicates they might be better at regulating their calorie intake. Overweight people may be less precise at regulating their food intake versus normal weight people.

Despite the limitations, this study at least hints that one of the reasons MRP's work is due to the fact they represent highly controlled portion sizes. In fact, one strategy that I use with some clients (I know my friend Spencer Nadolsky does this as well) is to use MRP's as a tool for when people hit a plateau in weight loss. In general, plateaus are more likely due to a loss of dietary adherence rather than factors such as metabolic adaptation. Thus, having people rely on MRP's can help improve dietary adherence as well as improve the accuracy of their self-report (as the portion sizes and calorie content of MRPs are controlled).

Regardless, even if the success of an MRP is completely due to the portion size, a high protein intake is still critical to maintenance of lean body mass during weight loss. Thus, even if a high protein MRP shake does not represent a satiety advantage, it still wins in regards to helping you keep your lean muscle.

PRIMARY REFERENCE

SECONDARY REFERENCES

Supplements have a structure that should be able to replace a lot of items and be able to transfer their role in exchange for materials, and diets should be able to demonstrate their positive impact well.