This article represents part 3 of a series on how insulin has been unfairly demonized by many in the nutrition field. If you have yet to read the first few parts, you can read Part 1 here, and you can read Part 2 here. In this article, I will discuss how dairy products are among the most insulinemic foods out there, yet do not promote fat or weight gain, which pokes holes in the hypothesis that carbohydrates drive fat accumulation through insulin secretion.

Dairy Products Are Insulinemic Yet Don't Promote Weight Gain

One of the premises of individuals like Gary Taubes is that carbohydrates stimulate fat accumulation by stimulating insulin secretion. I've already shown how this premise is flawed in the last two parts of my series. Namely, I showed how protein also stimulates insulin secretion (sometimes as much as carbohydrate) yet does not promote weight or fat gain. I also showed how the drug exenatide restores rapid-phase insulin secretion in diabetics yet promotes weight loss.

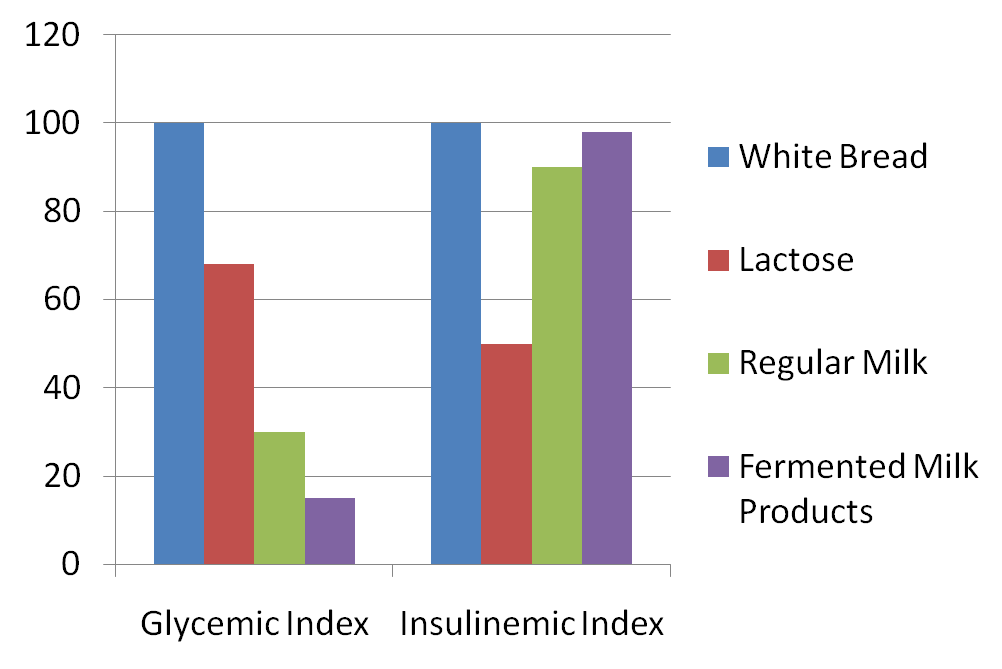

If the carbohydrate/insulin hypothesis were true, then we would predict that foods that are extremely insulinemic would be uniquely fat promoting. What many people do not realize is that dairy foods are among the most insulinemic foods out there. In fact, they create much greater insulinemic responses than you would expect based on their carbohydrate content. Not only that, but lactose, the primary carbohydrate in dairy foods, is actually low glycemic and produces slow rises in blood sugar (lactose has a glycemic index of 46 compared to white bread which is 100). In fact, the glycemic index of many dairy products is quite low, with full-fat milk at 39, skim milk at 37, ice cream at 51, and fruit yogurt at 41.

Despite the low blood sugar responses, dairy products create very large insulin responses. For example, in one study, dairy products created similar or greater insulin responses than white bread, despite the fact that the blood sugar response for some of the dairy products was 60% lower than the white bread. In this study, the researchers compared the glycemic and insulinemic responses between white bread, a low gluten/lactose mixture, a high gluten/lactose mixture, cod with added lactose, milk, whey protein with added lactose, and cheese with added lactose. All of the conditions contained 25 grams of carbohydrate and 18.2 grams of protein, except for the white bread and low gluten/lactose mixtures, which contained 25 grams of carbohydrate and 2.8 grams of protein. Thus, lactose was the carbohydrate in all of the conditions except for white bread.

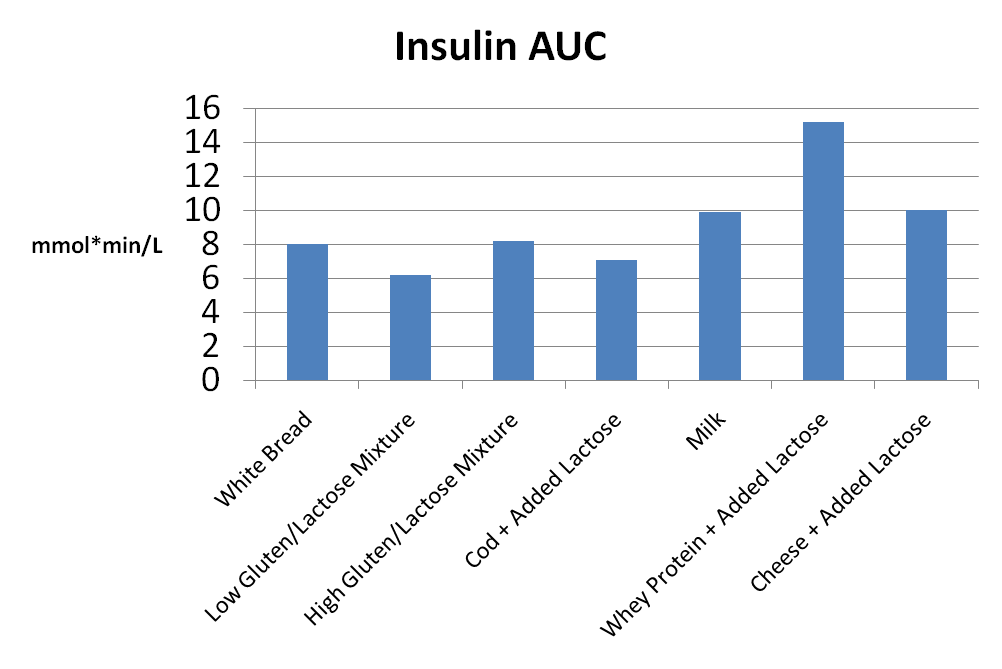

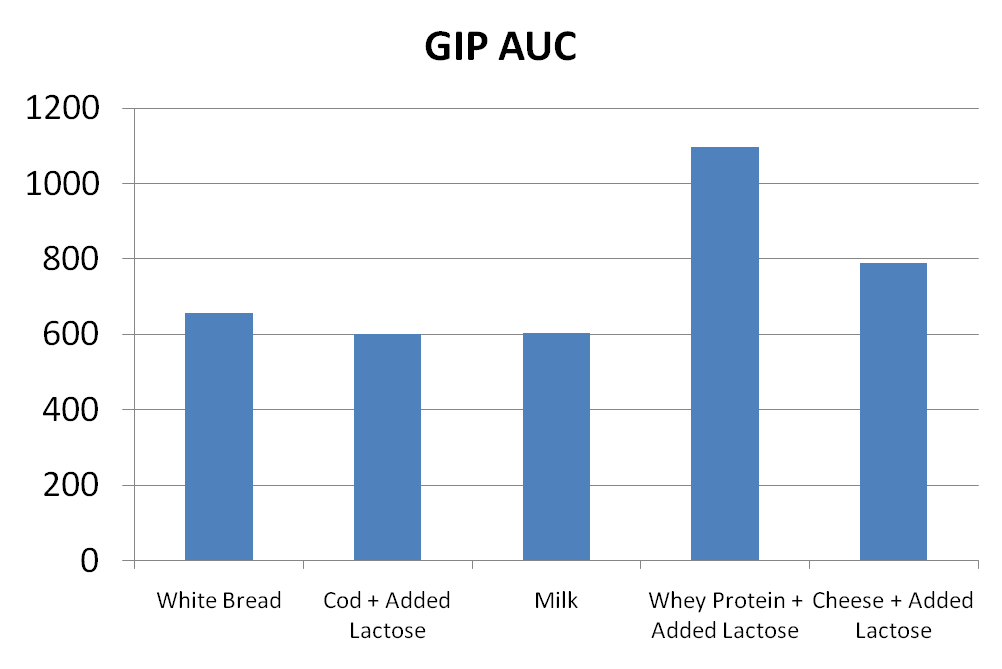

When you look at the insulin area-under-the-curve (AUC) for the various conditions, you can see that the dairy products actually created greater insulin responses than the white bread, despite having similar amounts of carbohydrate:

It is obvious that it is not the lactose that is responsible for the greater insulin response, because the gluten/lactose and cod/lactose mixtures resulted in similar or lower insulin responses to white bread.

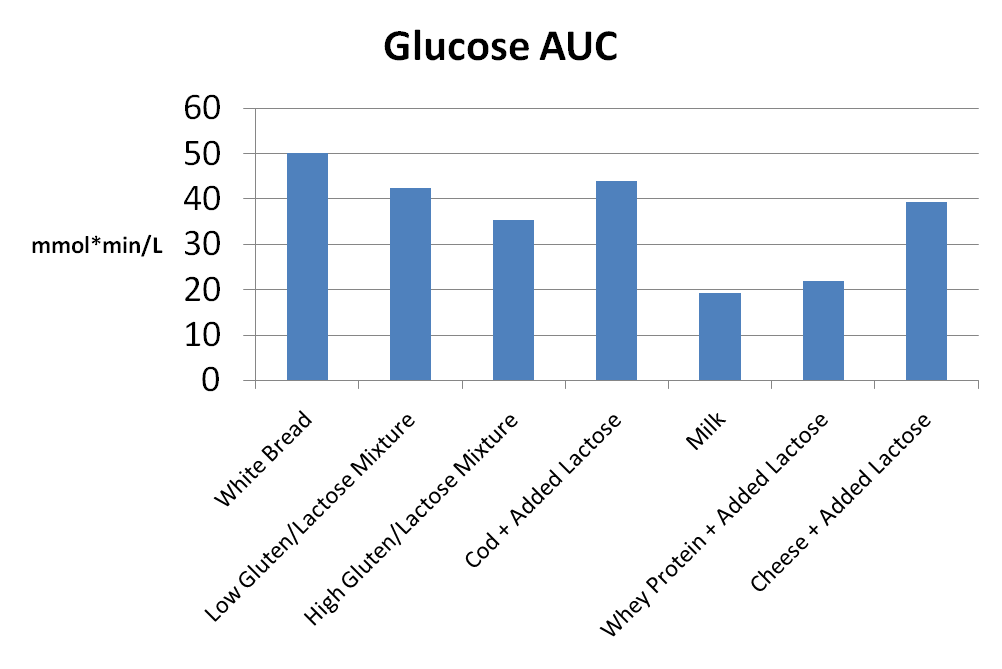

The blood sugar response was also not responsible for the greater insulin response. In fact, the blood sugar response was lower in all of the conditions compared to the white bread, with the milk creating the lowest blood sugar response yet 3rd highest insulin response:

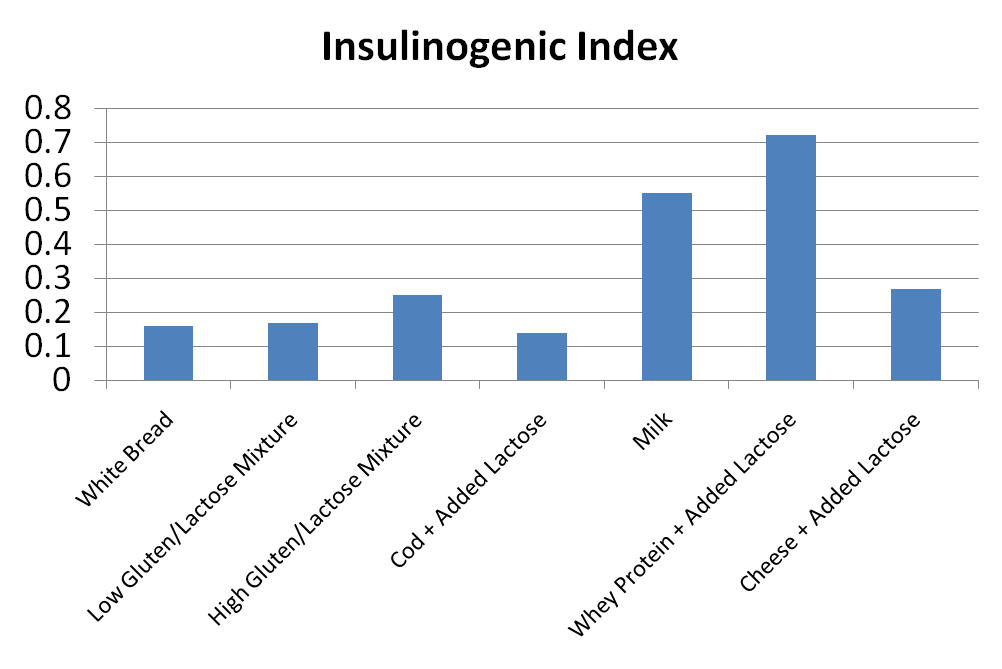

The insulinogenic index, which relates the amount of insulin secretion to the blood glucose response, was significantly higher in the dairy products, indicating that the dairy products stimulated much greater insulin secretion that you would expect based on the blood glucose response:

This is not the only study to show the insulinemic effects of dairy products. I showed in my previous article how whey protein, a dairy protein, created the highest insulin response compared to non-dairy proteins. In a study on type 2 diabetics, the inclusion of whey protein in a meal increased the insulin response by 31-57%, while the blood glucose response was reduced by up to 21%. In another study, the addition of 400 mL of milk to a bread meal increased the insulin response by 65%, despite the fact there was no change in the blood glucose response. In this same study, the addition of 200 or 400 mL of milk to a spaghetti meal increased the insulin response by 300%; again, there was no change in the blood glucose response. In fact, drinking milk with the spaghetti meal created an insulin response that was similar to white bread.

Here's the results of another study showing the glycemic and insulinemic indexes of milk compared to white bread:

Why Does Dairy Stimulate So Much Damn Insulin?

It is clear that dairy products stimulate large amounts of insulin secretion, as much or more than white bread. One of the reasons dairy products create large insulin responses is due to their amino acid content. In fact, the postprandial insulin response from dairy products correlates with the rise in branched chain amino acids leucine, valine, and isoleucine. I already pointed out in part 1 of this series how leucine will directly stimulate your pancreas to produce insulin.

Another reason that dairy products stimulate so much insulin secretion is their effects on a hormone called glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). Like GLP-1 which I wrote about in part 2 of this series, GIP is an incretin. This means that it is a hormone produced by your intestines that stimulates insulin secretion. Dairy products stimulate increased production of GIP. In the study I discussed earlier which compared whey, milk, and cheese to white bread, whey and cheese resulted in 21-67% greater GIP responses than white bread:

The above data illustrates one of the problems with the carbohydrate/insulin hypothesis...it assumes that carbohydrate is the primary stimulus of insulin secretion. However, it is clear that amino acids and incretins play significant roles in insulin secretion as well. And as I pointed out in part 1 of this series, the blood sugar response of a food only explains 23% of the variation in the insulin response. Thus, a lot more goes into insulin secretion than the blood sugar response from eating carbohydrate.

Dairy and Weight Gain/Loss

It is clear that dairy products are extremely insulinemic, moreso than many high carbohydrate foods. Thus, if the carbohydrate/insulin hypothesis were true, then we would predict that a diet high in dairy products should promote weight and fat gain. However, studies fail to show any relationship between dairy product intake and weight gain. For example, there is no relationship between intake of dairy products and BMI in Japanese women. In U.S. men, there is no relationship between an increase in dairy consumption and long-term weight gain. In perimenopausal women, high intakes of dairy products are actually inversely associated with weight gain (i.e, higher dairy product intakes are associated with less weight gain).

While these are observational studies, the results from controlled studies on animals and humans are similar. In fact, animal studies show less weight gain when they are fed dairy products. In mice, yogurt supplementation results in less weight and fat gain than controls on isocaloric diets. In another study, transgenic mice lost weight on energy restricted diets. The mice were then allowed to eat ad libitum (i.e., as much as they felt like). The mice fed dairy products regained less fat and weight during refeeding. In a third study, the intake of dairy products, but not a calcium supplement, decreased weight gain and body fat in mice fed a high-fat diet. In a fourth study, dairy protein attenuated fat gain in rodents fed a high-fat, high-sugar diet. In a fifth study, a dairy diet attenuated weekly weight gain in Sprague-Dawley rats.

Of course, these are animal studies. What about humans? In one study, low-fat dairy products did not promote weight gain, while high-fat dairy products did. Hmmm, could it be that the weight gain in this study was simply caused by excess calories and not insulin? In another study, increased intake of dairy products did not affect body composition. In a third study, increased intake of dairy products did not impair weight loss. In a one-year study, increased intake of dairy products did not affect changes in fat mass. In a 6-month follow-up to this study, high dairy product intake predicted lower levels of fat mass. In a 9-month study, increased intake of dairy products did not affect weight maintenance, but the high dairy group exhibited evidence of greater fat oxidation.

Why Am I Not Fat?

My own personal experience with dairy fits right in with the science. I consume a lot of dairy and have for many years. I go through 2-3 gallons of milk per week. I also go through a lot of Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, regular cheese, and whey protein. I have some type of dairy with just about every meal. Thus, I have large amounts of insulin flowing through my body pretty much all day. If insulin was truly the fat-promoting, weight-gaining hormone that some have made it out to be, then I should be obese by now. Yet, I am not...not even close.

Not only that, but the people who think insulin makes you hungry, that would imply that I should be starving all of the time with all of the insulin that is flowing through my body all day. Yet, I'm not.

Got Milk? Got Insulin!

The evidence is overwhelming that dairy products do not promote weight gain, and they actually inhibit weight gain in animal studies. This is despite the fact that dairy products produce very large insulin responses, as much or greater than many high carbohydrate foods. Thus, it is clear from this article, as well as my previous articles, that the carbohydrate/insulin hypothesis is incorrect. Insulin is not the criminal in the obesity epidemic; instead, it is an innocent bystander that has been wrongly accused through guilt by association.

Click here to read part 4 of my series, where I address the misconception of how insulin regulates blood sugar.

http://philmaffetone.com/updateondairy.cfm

Found this article on dairy. Quite a complex subject.

When doing studies, even the breed of cow has to be considered.

Somehow I am missing the point or I do not understand your logic reasoning: “I showed how protein also stimulates insulin secretion (sometimes as much as carbohydrate) yet does not promote weight or fat gain.” “If the carbohydrate/insulin hypothesis were true, then we would predict that foods that are extremely insulinemic would be uniquely fat promoting.” “The above data illustrates one of the problems with the carbohydrate/insulin hypothesis…it assumes that carbohydrate is the primary stimulus of insulin secretion.” There is just no way to come to your conclusions from the evidence you are presenting. You are talking about utterly unrelated facts here.… Read more »

There is just no way to come to your conclusions from the evidence you are presenting. It is quite simple to come to those conclusions. You are talking about utterly unrelated facts here. No, they are not unrelated. Insulin is blamed for weight gain primarily because of its suppression of lipolysis. Insulin suppresses lipolysis whether that insulin came from carbohydrates or from protein. In fact, it only takes small elevations in insulin to suppress lipolysis. This is not to also mention that lipolysis is irrelevant anyway. What really matters is fat oxidation…not lipolysis. You could have all of the lipolysis… Read more »

//Dairy products already contain sugar. It’s called lactose. This is also not to mention that most people don’t consume dairy products by themselves…they consume it with meals, which offers plenty of glucose to go along with the dairy. Yet research shows that dairy is associated with better weight control.// -The lactose in dairy is extremely minimal, especially fermented dairy. //This is also not to mention that sucrose is not extremely insulinemic. In fact, whey protein is more insulinemic than sucrose.// sucrose is less insulinemic than starch because it is 50% fructose and fructose doesn’t raise insulin. It is however, much… Read more »

It’s also worth noting that dairy (especially unfermented and low fat dairy) is far more insulinogenic than meat, fish or eggs. For example in this study (http://www.nature.com/ejcn/journal/v59/n3/full/1602086a.html) children were given strict diets of either lean beef or skim milk, and the skim milk diet induced hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance after just seven days. It sounds troublesome, but they used skim milk – a refined, fundamentally altered food. The meat had no such effect.

Read more: http://www.marksdailyapple.com/dairy-insulin/#ixzz2Ocxw4Gcp

Another author raised a good point about dairy which may be valid – “I think it’s more accurate to say that acute insulin spikes are different from chronically elevated insulin levels, especially when it comes to appetite regulation and metabolic derangement. Consider this study (2010 American Society for Nutrition, Effect of premeal consumption of whey protein and its hydrolysate on food intake and postmeal glycemia and insulin responses in young adults1,2,3) whose authors gave either whey protein isolate or whey protein hydrolysate to subjects 30 minutes before a pizza meal. Subjects given whey protein isolate, but not hydrolysate, reduced post… Read more »

I don’t think this really does anything to disprove Gary taubes contention that high carb diets promote more weight gain. Gary never said that Dairy promotes weight gain. It is not the insulin response perse which causes weight gain, it is the effect that the insulin response has on carbohydrates SPECIFICALLY. Eating high carbohydrate diets causes weight gain because the insulin response precipitates the conversion of glucose into adipose tissue to counteract elevated blood glucose. Eating dairy may provoke an insulin response, but in the absence of high blo od glucose, there is no sugar to convert into fat, and… Read more »

I was wondering, is it possible purpose of fat cells is not just storage but to convert excess sugars to fat since the cells are resistant to gluocse uptake in metabolic syndrome? so if you lower sugar/glucose load would that not be a incentive for the body to apoptosis the fat cells also considering fat cells job is to recycle cholesterol, store it when dietary sources are deplete and to store fat soluable minerals and vitamins when these tend to run low at times due to poor diets or dieting efforts? so increasing fat soluable vita/min rich foods and cholesterol… Read more »

Hi, Rose,

If cells are resistant to take up glucose, they can’t turn it into fat since they have to take up the glucose in the first place.

Also, fat cells do not commit apoptosis in the fashion you are describing. Fat cells in general either shrink or increase in size. Fat cells do not need to be “destroyed” to make an obese person thin. The triglyceride content of the fat cells simply needs to be dramatically reduced.

I have come to understand not all cells are resistant at the same time, fat cells are the last to become resistant hence the reason you stop gaining weight after awhile if all dietary habits remain the same. I have read some studies on pubmed and other journals (where you can read it for free on highwire press)that fat cells do apoptosize. also fat cells have other jobs to do besides energy conservation. I do have a question, is it possible to either be born or to develope an inability to produce vitad3 in the skin from unprotected sun exposure?… Read more »

I have just personally experienced the insulin response of dairy. I am on the 1st day of a carb cycling regimen where I had zero starchy carbs at my mid-day meal (I normally consume a carb heavy meal at this time). Apart from a slight light-headiness after the meal which I assume was down to the fact that my body is “used” to a high-carb meal (oats) at this time of day I felt fine all of the afternoon. I then remembered that I had earlier decided to consume the milk (skimmed) I would have consumed with the oats but… Read more »

Glad I found your posting. I’ve had a strange correlation between having milk (cereal portion) for breakfast and a moderate hypoclycemic event 3-4 hours later. For years I thought those events were in response to heavy exertion the previous day, but that was never consistant. I finally made the connection between the milk intake and hypoclycemic event and did this search. I can say without hesitation that I experience those events together if I don’t ingest more food within 2-3 hours of having milk in a large volume.

Thanks for your detailed info !

Glad you found the info useful!

very good article,

I am reading “The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman” from Ferris and he claims that dairy should be given up to lose weights, which is false according to this article!

Great, I can eat my daily part of cheese and my glass of milk without being guilty 🙂

Wow, thanks for mentioning that title, I’ve found it to be a fantastic book! It’s not so much original material as it is a distillation of the best knowledge that’s out there about fat loss, muscle gain, reaching orgasm, sleeping well etc., all taken from highly competent sources, many of which I could recognize from my previous encounters with their materials on the Web – Gary Taubes, Steve Pavlina, Nina Hartley etc. Awesome awesome find.

James, What’s the truth about hypoglycemia then? Henry Seale discovered reactive hypoglycemia when he noticed some of his patients had the same symptoms someone with diabetes has when too much insulin is injected. He theorized that certain people overeacts to carbs by producing too much insulin causing post-prandial blood sugar drops. He indeed fixed his hypoglycemic patients symptoms with a lower carb diet. Cheese is usually well tolerated by people with reactive hypoglycemia. But why? Does it mean that it doesn’t matter how insulinogenic a food is, only what foods an impaired pancreas overeacts to? Or maybe we should rethink… Read more »

Would eating fats with milk products reduce the insulin response they generate?(for example: eating cottage cheese with peanut butter)

I don’t know of any research that has looked at the effects of the addition of fat intake to dairy on the insulin response. This study showed a similar insulin response of full fat cheese compared to non-fat milk, suggesting that the addition of fat does not moderate the insulin response.

Should dairy products be limited by those with insulin resistance because of the insulin response they generate then?

Also, does casein show a high insulin response?

Yes, it does, but not as high as whey protein.

There is no evidence that dairy products should be limited by those with insulin resistance. In fact, there is some evidence that dairy has been found to be beneficial to those with insulin resistance.

Thank you very much for your time and answers.

I have recently been diagnosed with PCOS and one of the key dietary changes I was advised to make was to avoid cottage cheese because of the insulin response it creates(I had been eating 1-2 cups of a day). Would this recommendation be made on “old school” notions of dairy and insulin?

Yes, I would agree that this recommendation comes from the “old school” notion.